Build Your Own Campaign

Now that you’ve learned more about electronic monitoring and how it affects your community, it’s time to think about how to build a campaign that bans EM in your local area. Below is a step-by-step guide to everything you need to start leading a campaign.

How To Build An Unshackling Freedom Campaign: A Roadmap

Understand the Local Landscape – Become an expert on Electronic Monitoring in your community through research, networking, and interviews.

Set Goals – Figure out what success looks like for your campaign; what specific outcomes and changes would you like to see?

Identify key players – Define who is a key player–AKA who does this affect? Who has the power to change it?

Develop Messaging – Use your expertise to draft how you want to talk about EM locally, and who your audience is.

Make a Call To Action – Decide how you want people to join and contribute to the fight.

Talk to the Media – Use your messaging to talk to local reporters and journalists to spread awareness about your campaign to your community.

Take it Online – Use social media, websites, and even digital ads to spread awareness and grow your audience.

Organize IRL – Talk with and listen to the people who are most affected by EM–the community, and organize accordingly.

STRATEGIES + RESOURCES

Your starting point is information – you must become an expert on Electronic Monitoring in your county, city, community, and state.

To catalyze policy change, we need political decision-makers to understand and care about the harm EM is causing our communities. Right now, most elected officials and other decision-makers know very little about EM, meaning you will ultimately have to educate them.

To gain a foundational knowledge of EM in your jurisdiction you need to do research. In particular, you should:

- Talk to people who have been on the monitor or had their loved ones on the monitor-hear their stories, record them or make notes – This will be some of your most important evidence.

- Find out who is responsible for implementing and managing EM – This varies from place to place; it may be run by the sheriff, by a chief judge, or by a private company. You will need to know who the EM decision-makers are, who makes money from EM, who funds EM, and who has been promoting EM locally in the past and present.

- Access as much official data on EM as you can –Look for data on how many people are on a monitor, what documents or rules are shared by authorities with those who are on EM, what policies or ordinances local authorities have in place to implement EM, how much money is spent on EM each year, and who gets that money.

Without these fundamental details about electronic monitoring you will not be able to effectively mobilize people to your campaign or challenge the talking points offered by proponents of EM.

In a few jurisdictions, much of this information is public and easily accessible. However, in most places, you will have to file a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) or Public Records Request (PRR) to get even basic data on electronic monitoring.

Learn How To File a FOIA or PRR

Learn more about how to do research

Once you understand your landscape, you’ll want to define the goals of your campaign. Here are some questions to ask yourself to get started on your goals:

- Do you want to eliminate an existing electronic monitoring program?

- Do you want to stop a planned electronic monitoring program?

- Do you want to reduce the harm being done to people by an electronic monitor?

- Do you want to focus on getting people out of jail but make sure they are not put on a monitor?

- Do you simply want to educate people about the challenges posed by electronic monitoring and other forms of e-carceration?

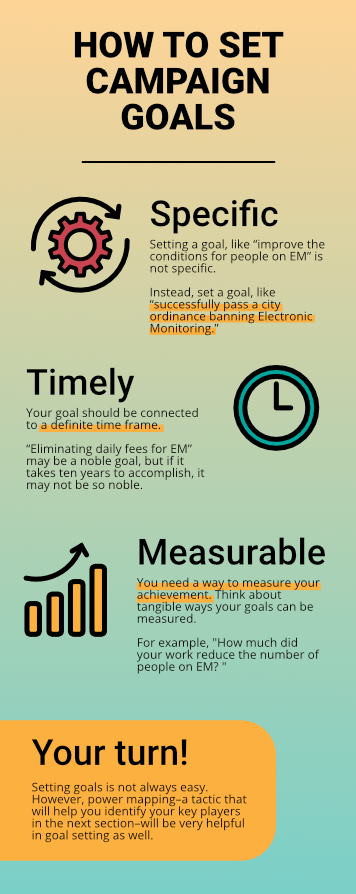

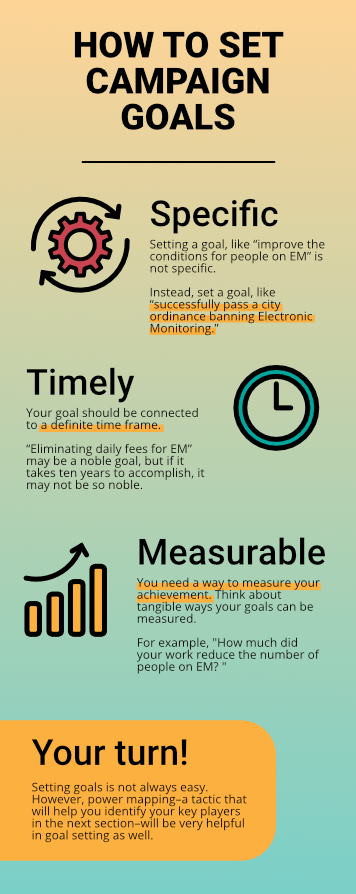

Your goals should be specific, within a time frame, and measurable

Specific

Setting a goal, like “improve the conditions for people on EM” is not specific. That could be satisfied by reducing the daily fees for EM by a dollar or by getting the entire EM program scrapped. Instead, set a goal, like “successfully pass a city ordinance banning Electronic Monitoring” or “successfully pass a city ordinance ensuring people can move about and around during the day.”

Within a Time Frame

Your goal should be connected to a definite time frame. “Eliminating daily fees for EM” may be a noble goal, but if it takes ten years to accomplish, it may not be so noble.

Measurable

You need a way to measure your achievement. Think about tangible ways your goals can be measured. For example:

- How much did your work reduce the number of people on EM?

- How much did the EM fees fall as a result of your campaign?

Setting goals is not always easy. However, power mapping–a tactic that will help you identify your key players in the next section–will be very helpful in goal setting as well.

To build a campaign challenging Electronic Monitoring you need to know who you are fighting against and who will join you in the fight. This means making a power map.

What is a power map – Power mapping is a visual tool used by social justice activists and advocates to identify the best individuals to target to promote social change. The role of relationships and networks is very important when advocates seek change in a social justice issue.

When creating a power map, you should identify which government bodies, business entities, and elected officials have a stake or a role in your local EM program – Typically a county governing body, like a County Board or Board of Supervisors will have to approve the establishment of any EM program and its annual budget for EM.

To successfully challenge Electronic Monitoring, you need to know where the members of these bodies stand on EM.

Important note: Law enforcement will also have a big say in the implementation of EM, even though they most likely don’t have a vote. However, you will need to counter their false narrative that EM is “good for public safety”.

- When mapping power, timing is also crucial. You need to know what time of year decision-makers are in action (i.e. when they review and pass budgets when they organize study sessions for different policy measures, what committees make those decisions, etc.)

- To win, you’ll need to persuade a majority of the decision-making body to be on your side. This means building relationships with allies and potential allies among the elected, especially those who oppose EM. Don’t forget to include these key players in your power map!

- A power map should also include a realistic assessment of the power and capacity of your organization.

- There are many ways to construct a power map. Click “Learn More and Access Templates” for more.

Learn More and Access Templates

It is absolutely crucial in building your campaign that you control your message, aka the content and materials you use to promote your work. Your message is how you communicate your goals and the purpose of your actions to various parties- your members, the media, the decision-makers. If you are pushing a piece of legislation, then your message must refer to that legislation in a consistent and clear fashion. You must also have some agreement on who actually speaks on behalf of the campaign.

Your messaging should be concise, clear, consistent, and actionable.

Concise

Focus on saying what you want to say in as few words as possible. You will typically have a short window to educate and persuade your target audience, and your messaging needs to be compact enough to fit into that window.

Clear

When talking about your campaign, you want your message to be crystal clear. Leaving any room for interpretation or confusion can hurt your chances of success. Community members, including impacted people, should be able to clearly understand your campaign and call to action.

TIP: Avoid complicated language. Your messaging should relate to people in the community. Avoid academic jargon.

Consistent

While every person who speaks on behalf of your campaign doesn’t need to say exactly the same thing, their messages need to have the same general content. If one member of the campaign says you want to end electronic monitoring and another says you are just fighting so people on EM can get more movement, your campaign cannot move ahead.

TIP: Try to ensure that your messaging is conveying the same message wherever it shows up.

Actionable

The number one goal for campaign messaging is to motivate your audience to take action. You don’t want to leave your audience wanting more. Instead, you’ll want to give them the tools they need to join our fight. This can be as simple as signing an online petition, doing a retweet, or signing up to attend a city council meeting.

Additional things to consider when developing your campaign messaging:

- What is the main point you want people to know about your campaign?

- What action do you want them to take?

- Who is your target audience(s)?

- Who is best suited in your organization to speak to those target audiences?

TIP: In considering who delivers your message you need to take into account the characteristics of the target audience as well as who represents your organization and your campaign. The public faces of your organization need to take into account race, gender, gender identity, and national origin, as well as the demographics of the people who are most directly impacted by the issue.

Be mindful of who you are talking to and without watering down your message, speak to their particular interests.

Key points in arguing against pretrial EM

Once you have your messaging and at least one call to action, you should start

creating a media and press strategy. You want to amplify your message and call

to action to reach your target audience(s) as much as possible.

First, build local media contacts

Local media is one of the best vehicles to gain support in your community.

Building up a list of reporters, deejays, talk show hosts, podcast producers,

community radio, and TV stations can be a powerful force. Plus, being

interviewed on radio or TV can be a very empowering experience for impacted

people. While many activists don’t pay much attention to local media, elected

officials often do.

Next, think about writing an Op-Ed

Op-eds or opinion pieces provide an opportunity to get your message out to a

wider audience. These are most effective when they respond to specific issues

or moments in the struggle over EM.

Op-eds can:

- Present new or correct information about the issue.

- Present a new or counter view on an issue that the media has not seen.

- Offer an opportunity for your organization and your campaign to reach new

audiences.

- Highlight an upcoming action of your campaign or issue that is important to

your campaign.

Most publications have specific guidelines and word counts. Before you write

an Op-ed, be sure to research the requirements of the publication you are

targeting. It is helpful to speak directly with the person in charge of Op-eds,

as they often have extra information that can help you get your piece placed.

Here are a few examples of Op-eds on Electronic Monitoring:

Creating a digital component to your campaign can be a gamechanger, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. Here are a few digital elements you should consider when building your campaign:

Social Media

Social media is a perfect opportunity to reach your target audience(s) where they likely are already at. A good social media campaign strategy is authentic, culturally relevant, and aligns with the values and mission of the campaign.

TIP: It’s better to be consistent than constant for digital advocacy on social media. Focus on educational content that is either highly shareable or save-worthy to engage best with your target audience(s).

Website

Having one central digital home for every part of your campaign is crucial. Even if it’s simply a subpage of your organization’s existing website, having somewhere to direct your audience that is user-friendly, consistent with your campaign’s brand, and actionable will help you convert followers into volunteers and activists.

Digital Ads

Growing your digital presence organically is a struggle on today’s social media platforms. Utilizing paid digital ads–in an ethical way–can help you narrow your target audience, and engage with the communities who care most about your campaign. Digital ads can also help you grow your following, which in turn can help build media and policymaker relationships.

Your campaign should have a people-centered organizing component that runs parallel and simultaneous to all other aspects.

Organizing doesn’t have to be complicated or expensive; instead, focus on what feels natural and authentic to your organization and community.

For example, you mobilize allies and extend your base by providing opportunities for everyone in your campaign to engage in action whether it be organizing demonstrations, attending public meetings, sending messages to decision-makers, whatever will build your power and keep your members active.

Support what’s happening on the ground

Campaign Case Studies

There are a number of jurisdictions that have attempted to address the issues of pretrial detention, cash bail, and conditions of release such as electronic monitoring. Here we present some details of two cases: the Illinois Pretrial Fairness Act and the Bail Elimination Act of 2019 in New York.

Illinois Pretrial Fairness Act

The Illinois Pretrial Fairness Act was signed into law in February of 2021. The Act was the result of more than five years of grassroots organizing in Chicago and across the state. Cook County, where Chicago is located, had one of the largest and most punitive pretrial EM programs in the country with many people on 24/7 lockdown. While the act addresses a full range of pretrial issues, the advocates had a clear cut position on electronic monitoring-that it was a form of incarceration, that no one who was released pretrial should be on a monitor and that resources should be reallocated to effective programs outside the authority of the state instead of being used to pay for EM. For a broad overview and assessment of the campaign for the Act, see On the Road to Freedom, pages 55-60.

Here are some key points to draw from the campaign:

- While the campaign to end pretrial detention and end money bonds began largely as a project of the abolitionist Chicago Community Bond Fund, the Fund saw the need to draw in a broader spectrum of organizations which became the Coalition to End Money Bond. The coalition included a range of advocates and organizations with varying political perspectives but with the common aim of eliminating cash bonds. Eventually, they built a statewide network and held meetings across the state with advocates and impacted people.

- The Bond Fund did a deep study of pretrial electronic monitoring in Cook County (where Chicago is located). They published their findings in a report in 2017. They included experts from outside their organization to shed light on electronic monitoring.

- The Bond Fund and the Coalition shared stories of impacted people like Lavette Mayes, Timothy Williams, and Rashanti McShane. They shared these stories through social media as well as in live events. These helped mobilize popular support for opposing EM.

- Coalition members spent hundreds of hours engaging state legislators and advocates with a consistent message-end money bond, with no punitive conditions for those released pretrial. They also spent hundreds of hours in meetings to develop their strategy and plans of action.

- In the end, the bill passed, making Illinois the first state in the US to ban money bonds.

- Supporters of the bill were not able to gain support for the full elimination of pretrial electronic monitoring. They settled on a compromise that guaranteed everyone on pretrial monitoring movement from their house a minimum of two days a week. The bill also stipulated that the court must hold a full-fledged hearing to place someone on pretrial electronic monitoring and if they want to hold them on that monitor for more than 60 days, they must hold another hearing to extend the EM. Previously, there were no court hearings and a judge could just issue an order.

Their campaign raised two important issues:

- Often, the issue of electronic monitoring is linked to other issues like pretrial release, cash bail, immigrant rights, youth justice, or conditions of parole. EM may not be the main issue but it should not be forgotten or simply accepted without qualification as a necessary compromise.

- If you support an abolitionist perspective, you need to be clear on what the overall implications of a legislative or policy measure you are supporting are. Often asking some key questions about the reform will help you decide. Here, we summarize four key questions suggested by the abolitionist organization Critical Resistance in their document On The Road to Freedom, in assessing legislation or policy:

- Does it weaken the system’s power or means to jail, surveil, monitor, control, or otherwise punish people?

- Does the reform challenge the size, scope, resources, or funding of the prison-industrial complex?

- Does the reform maintain protections for everyone? (this means not penalizing one group further while advancing another-an example would be eliminating EM for people with non-violent charges and refusing release for anyone with a charge categorized as violent).

- Does the reform shrink parts of the prison-industrial complex by reducing budgets and/or the power of those who drive and benefit from incarceration?

New York Bail Elimination Act of 2019

New York passed bail reform legislation in 2019, through the efforts of grassroots organizations as well as advocates and elected officials. A big part of the push for bail reform was the case of Kalief Browder. He spent three years in Rikers Island jail because he could not afford the bail of $3,000 set for his alleged theft of a backpack. Ultimately, his case was dismissed but the trauma of his jail experience triggered his suicide in 2019. The legislation did eliminate cash bail, but only for a small portion of those in pretrial detention-those with misdemeanor charges and those with certain non-violent felonies. The bail reform took away the discretionary power of judges to deny people release if they had those specified charges.

The Act promoted the use of “release under non-monetary conditions” which was not in the statute before. This opened the door to more use of electronic monitoring which had not been used very frequently in New York in any case. To further block the use of EM, advocates pushed a clause in the legislation that banned the use of local government funds to pay for the services of private electronic monitoring companies. Since virtually all electronic monitoring is run by private companies, this effectively blocked any expansion of EM for those released under the bail reform.

A year later, a backlash hit from both Republicans and moderate Democrats. They succeeded in restoring the discretion of judges to impose bail on certain people largely by reducing the list of charges for which an individual had to be released but the restrictions on private companies providing EM remained. Moreover, the act contained no provision for funding of services desperately needed by those in jails-housing, healthcare, mental health care facilities. Instead of spending on those services, the city of New York voted to spend $8.7 billion to build four new jails in the city to replace Rikers.

Key issues raised:

- Legislation can be crafted to ban something through indirect tactics. Instead of outlawing EM, the legislation blocked contracts with private companies for EM. But since only private companies offer EM, it was the equivalent of a ban.

- Once a law is passed about EM there is likely to be a backlash to at least roll back some portions of the legislation. People involved in campaigns should be aware of this.

- Electronic monitoring is important but it is only one piece of the massive system of incarceration and punishment. If we block the implementation of EM while billions go to jail building, it is definitely a limited victory.

TOP