Before I got on a plane last month to visit La Union del Pueblo Entero on the border of Texas and Mexico, I’d already had a story about the place in my head. It goes something like giant steaks and ribs, racist sunburned people, pickup trucks and the occasional buzz of a low rider’s hydraulics. Okay, I’m exaggerating a little—I’ve known of some really awesome organizing in Tejas for years now. My point is that there is often a shared narrative about people, places, and things, usually informed solely by the news and entertainment media; the Food Network; music videos (for those of you who also went through a Chicano rap phase); the unfortunate phenomenon of George W. Bush; and, what we hear from others.

Before I got on a plane last month to visit La Union del Pueblo Entero on the border of Texas and Mexico, I’d already had a story about the place in my head. It goes something like giant steaks and ribs, racist sunburned people, pickup trucks and the occasional buzz of a low rider’s hydraulics. Okay, I’m exaggerating a little—I’ve known of some really awesome organizing in Tejas for years now. My point is that there is often a shared narrative about people, places, and things, usually informed solely by the news and entertainment media; the Food Network; music videos (for those of you who also went through a Chicano rap phase); the unfortunate phenomenon of George W. Bush; and, what we hear from others.

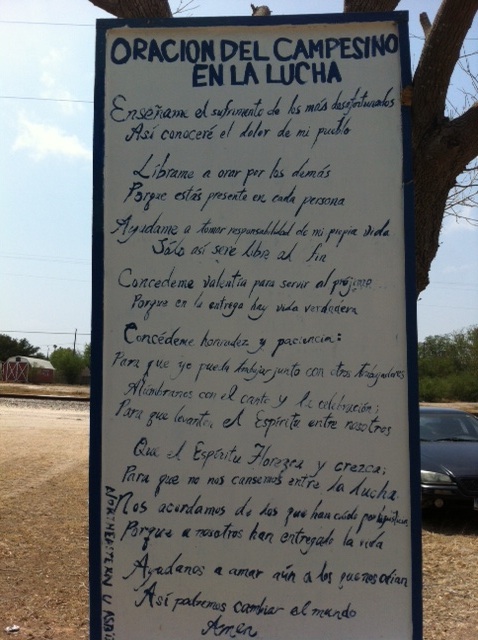

In a state that has long been a symbol if not caricature of the United States abroad, and by proxy the U.S. ideals of democracy and freedom that it imagines itself to protect, the irony is palpable. For the individuals and families who live in the colonias of Texas —who are almost 99 percent Latino—their “land of the free” is comprised of unincorporated subdivisions along the border that typically lack basic infrastructure, clean water, unemployment and drop out rates both at about 50 percent. For these families, there are a whole host of harmful narratives that perpetuate deeply rooted racist, classist, and xenophobic assumptions.

Along with my co-trainers and fellow technical assistance providers Kenyon Farrow from the Praxis Project and Pancho Arguelles of the Communities Creating Healthy Environments initiative, I had the privilege to travel to San Juan, TX to deliver training and technical assistance to staff and community leaders of LUPE. LUPE, founded by Cesar Chavez, has decades of experience in organizing the communities that live near the U.S.-Mexico border. Their colonia work alone organizes 6,000 residents of the colonias.

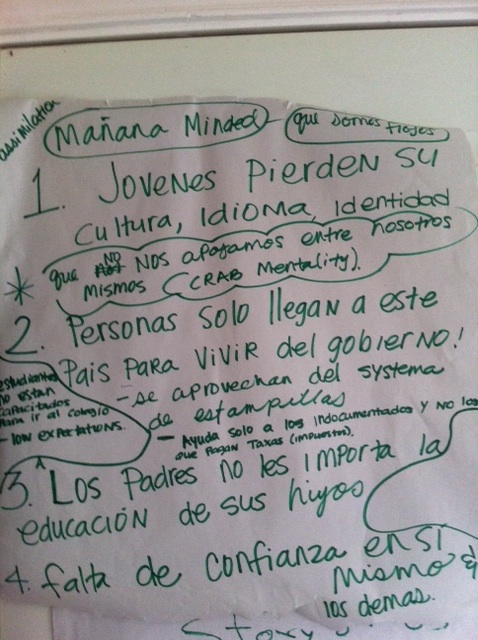

During the training, LUPE members shared familiar and contradictory mainstream narratives about their communities like “illegals…criminals taking advantage of the system and social services…pouring across the border” and simultaneously, “hard workers…family-oriented.” These dehumanizing and wedging narratives thrive within the meritocratic, personal responsibility frames of the U.S. have real impacts on families, such that securing even basic human rights and basic “first world” infrastructure—like streetlights for public safety—is an uphill battle for LUPE organizers and members.

During the training, LUPE members shared familiar and contradictory mainstream narratives about their communities like “illegals…criminals taking advantage of the system and social services…pouring across the border” and simultaneously, “hard workers…family-oriented.” These dehumanizing and wedging narratives thrive within the meritocratic, personal responsibility frames of the U.S. have real impacts on families, such that securing even basic human rights and basic “first world” infrastructure—like streetlights for public safety—is an uphill battle for LUPE organizers and members.

Narratives are created and transmitted outside the realm of fact. Like anything ideological in nature, narratives about people, places, and events can mutate and thrive from generation to generation, often contrary to actual experiences and interactions and even contradicting simultaneous narratives. For example, in Ideology and Race in American History, Barbara Fields talks about European slave traders who “were capable, as are all human beings, of believing things that in strict logic are not compatible. No trader who had to confront and learn to placate the power of an African chief could in practice believe that Africans were docile, childlike, or primitive.” Similarly, Asian/Americans are triangulated as deferential “model minorities” in a system of white supremacy and the oppression of African Americans, while simultaneously being a “yellow peril” via the global economy or as a cunning, backstabbing hacker on the latest episode of the popular ABC show Revenge.

Polarizing stories about communities of color translate into real-life conditions, and serve to pit poor U.S.-born and non-U.S. born people of color against each other (as we saw recently with Ethan Bronner’s reporting on farmworkers in Georgia while rendering invisible dominant structures of power and unequal access. Relying on facts alone will not advance a transformative narrative—but speaking to shared values and elevating the humanity and right to dignity of all families might. Check out this Center for Media Justice storytelling worksheet to carry your message and remember—identifying, understanding, and tackling the assumptions of the media, your opponents, potential allies and other audiences are fundamental to changing the story.