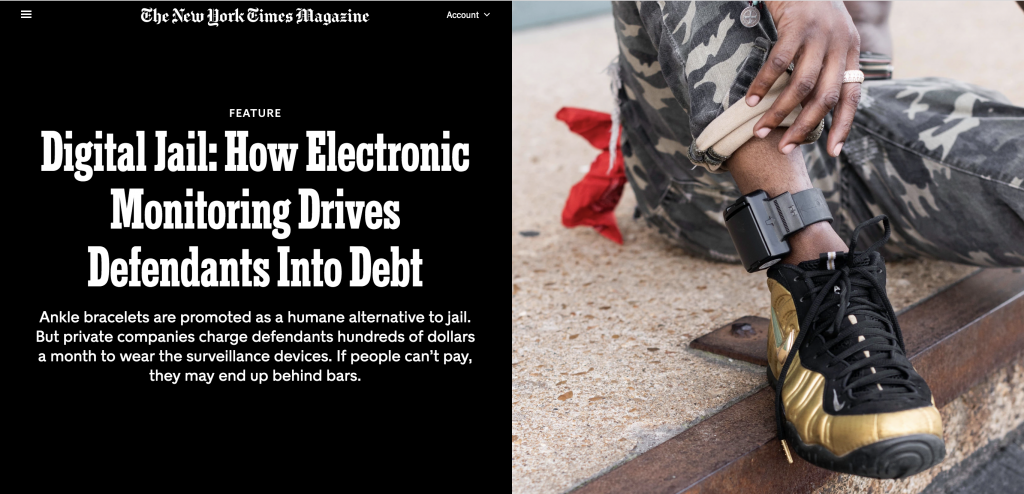

Ava Kofman’s recent ProPublica/New York Times feature, Digital Jail: How Electronic Monitoring Drives Defendants Into Debt, stands as the most comprehensive journalistic examination of electronic monitoring to date. It does a wonderful job of framing the horrific personal story of Daehaun White, bringing to light the injustice of user fees, the restrictions on freedom that come with monitors, and the way electronic monitoring (EM) replicates the conditions of steel and concrete cages in people’s communities.

Apart from chronicling this moving story, the feature also makes important points highlighting the expanding use of EM, especially in the pretrial setting; the growing capacity of GPS and other technologies in sync with the expansion of the surveillance state and the fact that even in the absence of significant hard data, we can safely conclude that EM disproportionately impacts people of color, especially Black people. Kofman also stresses how politicians across the spectrum are buying into the use of EM as a techno-quick fix.

The piece includes an impressive range of people as well, drawing in examples from various parts of the country, convincingly demonstrating that what happens in St. Louis is not an aberration but part of a national trend. (Full disclosure: I was also interviewed by Kofman for this piece).

I especially appreciated two details in the feature. First, when framing predictions about electronic monitoring it squarely places EM in context, recognizing that we can’t expect electronic monitoring as a technology to stand still nor can we expect it to be anything other than punitive unless we have a paradigm shift away from punishment. Secondly, I really loved the closing line, where the protagonist of this piece reminds us that EM is part of how he as a young Black man is criminalized “for living…for being me.”

Despite these strengths, there are also elements in the article which risk mirroring some of the mistakes made in analyzing mass incarceration in its cage form—and it’s important for us to unpack these potential pitfalls. The first is the centering of “user fees” as a seemingly primary problem, which might lead a reader to conclude that the major culprit in this socio-drama is EMASS and other similar companies—rather than a racist system of punishment. The “private prisons are the main problem” trope has always been attractive to some because it provides a clearcut target and solution, but it is ultimately misleading. This thinking can result in a view that if we were to just get rid of the fees, electronic monitoring wouldn’t be so bad.

Yet, whether we are dealing with prisons or electronic monitoring, the central issue remains freedom and priorities. To change either of these requires a major transformation in the philosophical framework that informs and inspires the state, not the simple removal of profiteers. These profiteers are, after all, the junior partners of the politicians and government officials who motivate budget lines and drive policies to favor these culprits. No private prison company can run a prison without a whole government/law enforcement apparatus to push people into cages. No electronic monitoring company can make money without judges, county boards, and state legislatures to approve the use of these ankle shackles and all the policies that go with it. It is not about privatization, it is about a lack of freedom.

The second trope that mainstream misreadings of mass incarceration risk furthering is the erasure of the fight back. For years, the voices of formerly incarcerated people and activists on the ground were missing from the descriptions of the horrors of mass incarceration. Concerned people, even those directly impacted, were often left feeling helpless by overwhelming data and horror stories with seemingly no possible resolution. The narrators of this tale typically didn’t bother to note that there were people at the grassroots level fighting back. Only when formerly incarcerated people started to organize did we get some media attention from places like the New York Times. What’s still missing from features like Kofman’s though are the grassroots efforts of folks like the National Bail Fund Network, the National Bailout and powerful anti-jail groups in New York, San Francisco and other places pushing back against the use of pretrial EM. Just two years ago, our Challenging E-Carceration project managed to get over 60 national and grassroots organizations to sign onto Guidelines for Respecting the Rights of People on Electronic Monitors. It’s important to highlight this activity, to let people know there can be an alternative.

Much to their credit, The New York Times and ProPublica have an interest in contributing to this work, having already set up an online platform for people to share their experiences of electronic monitoring. And it is these stories that will not only complete our picture of EM but give us the evidence we need to build an effective movement to resist e-carceration. We look forward to more from this initiative and hope that the future work it informs will expand the vision of digital prisons and help more people recognize that electronic monitoring is not an alternative to incarceration but an alternative form of incarceration; a form we accept at the expense of the very same Black, brown, and poor populations who have been the primary occupants of Department of Corrections’ cages.

James Kilgore is a MediaJustice Fellow. Learn more about the #NoDigitalPrisons campaign.