By Nekima Levy-Pounds, Esq.

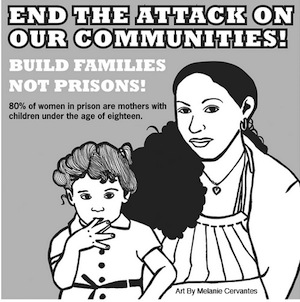

Currently over 2.7 million children in the U.S. have a parent who is incarcerated. As a result of the failed war on drugs that began in the  1980s, an increasing number of children have not one, but two incarcerated parents. This phenomenon has occurred largely as a result of drug conspiracy laws which make it easier for women to be charged with drug crimes for peripheral involvement in drug activity such as answering telephones or stashing drugs for a boyfriend or spouse. To put this in perspective, the Bureau of Justice Statistics notes, that from 1986 to 1996, the number of female prisoners sentenced to state prisons for drug crimes ballooned from 2,370 to 23,700. The number has continued to grow steadily since then. Sadly, many of the women who are caught in our nation’s drug war are mothers of children under age 18 and were often the sole primary caregiver of their children prior to being incarcerated.

1980s, an increasing number of children have not one, but two incarcerated parents. This phenomenon has occurred largely as a result of drug conspiracy laws which make it easier for women to be charged with drug crimes for peripheral involvement in drug activity such as answering telephones or stashing drugs for a boyfriend or spouse. To put this in perspective, the Bureau of Justice Statistics notes, that from 1986 to 1996, the number of female prisoners sentenced to state prisons for drug crimes ballooned from 2,370 to 23,700. The number has continued to grow steadily since then. Sadly, many of the women who are caught in our nation’s drug war are mothers of children under age 18 and were often the sole primary caregiver of their children prior to being incarcerated.

It is not difficult to imagine that children of incarcerated parents suffer mentally, emotionally and psychologically as a result of a parent’s incarceration. According to a study conducted by the Vera Institute of Justice, children of incarcerated parents experience a grieving process called “ambiguous loss” which is similar to experiencing the death of a parent. The emotional and psychological effects of long term parental incarceration may cause some children to act out in school, use drugs as a coping mechanism, and come into contact with the juvenile or adult criminal justice systems. Sadly, African American children are particularly vulnerable as they are nine times more likely than white children to have an incarcerated parent.

The devastating effects of parental incarceration are arguably made worse when children are unable to maintain contact with a parent or loved one who is behind bars. This occurs because state and federal prisons are often located in rural areas which are sometimes hours away from the nearest major metropolitan area. Families with limited means and inadequate access to transportation may find it difficult to physically travel to a prison to visit a loved one who is incarcerated. In cases in which a person has received a federal prison sentence, a prisoner has no control over where he or she will be sentenced to serve his or her time. Thus, a federal prisoner could be required to serve his or her time in a prison that is literally thousands of miles away from home in another state, without regard for whether he or she has small children at home. Given the limited income of most prisoners and their families, telephone contact may be one of the only options available to ensure regular communication between prisoners and their family members. Unfortunately, the exorbitant cost of telephone calls to and from prisons make it difficult, and in some cases nearly impossible, to maintain contact by phone. The high cost of phone calls to and from prisons means that poor families who desire to maintain telephone contact with incarcerated relatives may have to choose between buying groceries and paying the price for telephone calls to and from prison. This is a travesty of justice.

For children who are longing to hear the voices of their mothers or fathers who are behind bars, the ability to have regular telephone contact could mean the difference between a child having hope or a child experiencing anguish during a parent’s incarceration. It could also mean the difference between a child who feels loved in spite of a parent’s incarceration and a child who feels abandoned. Thus, the importance of ongoing telephone contact between an incarcerated parent and a child cannot be underestimated. Children deserve to hear the voices of their parents on a regular basis, even during parental incarceration. Regular phone contact will allow continuity in the relationship between incarcerated parents and their children and will help to mitigate suffering on both ends of the phone line. This is not a matter of catering to persons behind bars. This is a matter of justice.

Nekima Levy-Pounds is an Associate Professor of Law at the University of St. Thomas Law School and founder and director of the Community Justice Project, an award-winning civil rights legal clinic.

Nekima Levy-Pounds is an Associate Professor of Law at the University of St. Thomas Law School and founder and director of the Community Justice Project, an award-winning civil rights legal clinic.