October 21 2015Electronic monitoring is touted as a potential solution to the problem of mass incarceration. Not only would it decrease prison and jail populations, but it’s also cheaper on a per-person basis, saving states money, and would put individuals back in their communities and with their families. But a new report cautions against the use of electronic monitoring, arguing that it’s a deeply flawed alternative with substantial hidden costs.

The report, Electronic Monitoring Is Not The Answer: Critical reflections on a flawed alternative, comes from James Kilgore — a researcher, writer, and criminal justice activist. Kilgore writes from firsthand experience: he is a formerly incarcerated felon and wore an ankle bracelet as a condition of his parole.

Kilgore’s report is an important contribution to an underdeveloped conversation. Though electronic monitoring began over three decades ago, and has proliferated since, research has largely focused on how electronic monitoring affects the recidivism rates of sex offenders, or on how the monitoring devices could operate more efficiently. “Little effort has been made to examine how a monitor affects the individual wearing the ankle bracelet, let alone their families and communities,” argues Kilgore.

Electronic monitoring in the criminal justice system began in 1983 in New Mexico. This monitoring typically takes one of two basic shapes: the device either relies on a radio link to a nearby base station or GPS to operate and monitor an individual. Today, it’s estimated that about 300,000 individuals participate in an electronic monitoring program every year. However, understanding the prevalence and scope of electronic monitoring in the criminal justice system remains a challenge. As Kilgore notes, there is “no national database of monitoring usage or precise composite figures for those being monitored.”

As Kilgore argues:

“electronic monitoring has experienced a process of ‘net-widening.’ Policy makers and entrepreneurs have found new situations to apply an ankle bracelet. Thus, electronic monitors appear not only as a condition of parole, probation, and pretrial release, but also in response to truancy violations, juvenile court involvement, and domestic violence as well as during the waiting time before judgment in asylum or deportation cases.”

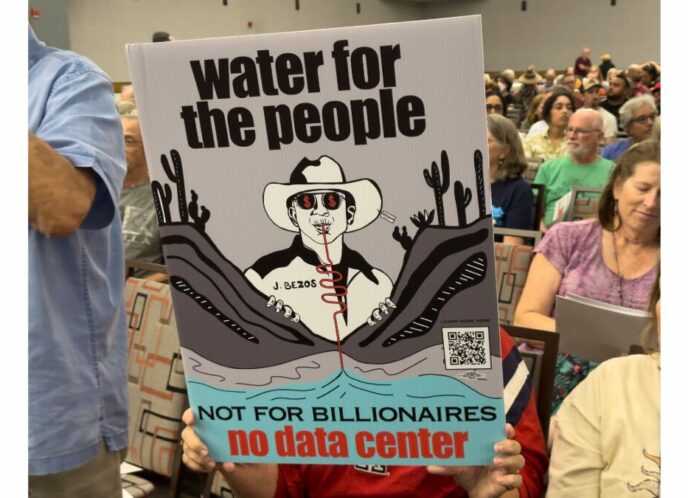

And as electronic monitoring devices have spread across the criminal justice system — from pretrial release to parole and beyond — some jurisdictions have begun turning to offenders to fund the new devices. In these models, not only are individuals monitored by law enforcement, but they also are required to pay a fee for being monitored.

Some jurisdictions have begun turning to offenders to fund the new electronic monitoring devices.

Take the example of Antonio Greene, a resident of Lugoff, South Carolina recently profiled by the International Business Times. Green drove without a license to pickup his mother after her car broke down. “Green was arrested … where he waited overnight until his elderly mother was able to post the $2,100 to bail him out. A condition of Green’s bail, ordered by the judge, was that Green wear — and pay for — an electronic monitoring device.” And Antonio Greene’s experience isn’t uncommon: a joint survey by NPR, NYU’s Brennan Center for Justice, and the National Center for State Courts found that in “all states except Hawaii and the District of Columbia, there’s a fee for the electronic monitoring.”

For state and local agencies looking to decrease the financial burden of overcrowded prisons and jails, electronic monitoring seems like an attractive alternative. Not only does electronic monitoring cost less than incarceration in the first place, but offender-funded models also allow state and local agencies to offload the cost of the monitoring itself from their checkbook to the offender’s.

But there are few electronic monitoring guidelines and best practices in place — let alone policies that work to protect individuals’ civil and human rights. As Kilgore writes, “though most jurisdictions operate without any guidelines or principles,” the guidelines that do exist “tend to be statutes that may empower state or local authorities to use EM [electronic monitoring] in certain cases, spell out the details of equipment to be provided, or list the penalties for violations of EM rules.”

Without clear rules, the monitoring can be arbitrary and punitive. Individuals under electronic monitoring may be told not to “shop and attend a movie during the same outing,” or not to “go to a hospital in an emergency without first obtaining permission from the parole officer,” or might “not b[e] able to shower because the shower was out of the range of the signal of the ankle bracelet.”

Without clear rules, electronic monitoring can be arbitrary and punitive.

As New York University Law School professor Erin Murphy argues, “whereas physical incapacitation of dangerous persons has always invoked some measure of constitutional scrutiny, virtually no legal constraints circumscribe the use of its technological counterpart . . . [courts] largely overlook the significant threat to liberty posed by technological measures.”

That legal disconnect may slowly be changing.

The Supreme Court recently took up Torrey Dale Grady’s case — a twice-convicted sex offender who’d been ordered to wear an electronic ankle bracelet tracking his whereabouts for the rest of his life. The important question in Grady’s case was whether, by imposing continuing, lifetime monitoring of his movements, the government had impinged on his Fourth Amendment rights. The Court held that a state “conducts a search when it attaches a device to a person’s body, without consent, for the purpose of tracking that individual’s movements.”

Policymakers, advocates, and law enforcement must ultimately address more fundamental questions: when and where, if at all, should electronic monitoring be used as an alternative to incarceration? As more than 130 police chiefs, prosecutors, and sheriffs call for reductions in prison populations, the question is an urgent one.