In 1994 I was a student at Macalester College. For a winter internship I started working at the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy editing a book for Kristin Dawkins on a trade Agreement called NAFTA. Recently ratified, NAFTA had just entered into force on January 1, as the Zapatista National Liberation Army occupied six towns in Chiapas, calling NAFTA a “death certificate.”

Like many people born in the Global South–who have been permanently displaced to the U.S–the long arm of globalization is intimately involved in my life. In fact, my life in the U.S is the by-product of U.S. trade policy that capitalized on the poverty of the Global South to exploit our services, undermine our regulations, displace our communities and solidify control over our natural resources–while simultaneously implementing a level of corporate investment rights unprecedented in scope and power. We were force-fed an ideology that promoted corporations as agents in the spread of democracy, but we knew better.

Over the next decade, the Zapatistas helped to popularize a growing critique of the free market agenda of corporate globalization, known as “neoliberalism.” At the same time, what started as a college internship turned into 10+ years of studying and organizing against neoliberalism within the U.S. and globally. Nearly all of this time I worked in rural communities—specifically food processing towns. The workforce was usually from southern Mexico or Central America, often subsistence farmers who had been forced North by the ‘dumping’ of U.S. corn in their markets.

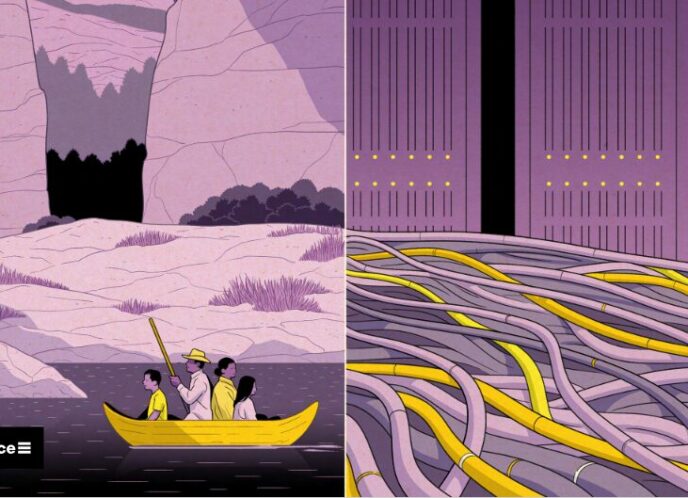

These (im)migration patterns reflected the incongruity of a model of global economic integration, whose push-pull factors reduced the ability for sustainable livelihoods in the Global South, while simultaneously creating the need for cheap labor in the Global North. Recruited by the food-processing companies themselves, the workers arrived in the Midwest to cut and pack chicken, beef and pork for long hours with little pay. Together we protested Monsanto’s terminator seed, marched against the FTAA in Miami and at the 5th ministerial of the WTO in Cancun. Everyone wanted to return home one day, so our organizing was transnational. We worked across borders to improve our lives in the U.S. and our countries of origin.

These (im)migration patterns reflected the incongruity of a model of global economic integration, whose push-pull factors reduced the ability for sustainable livelihoods in the Global South, while simultaneously creating the need for cheap labor in the Global North. Recruited by the food-processing companies themselves, the workers arrived in the Midwest to cut and pack chicken, beef and pork for long hours with little pay. Together we protested Monsanto’s terminator seed, marched against the FTAA in Miami and at the 5th ministerial of the WTO in Cancun. Everyone wanted to return home one day, so our organizing was transnational. We worked across borders to improve our lives in the U.S. and our countries of origin.

In 2004, I transitioned from rural organizing into media policy. At first many people wondered what media policy had to do with globalization? Net neutrality, data caps, spectrum auctions and reclassification were abstract concepts. What did that have to do with globalization? “What happened to NAFTA, NAFTA we don’t hafta?” they asked. For me the through-lines were present. What I grasped was the way in which media and telcom perpetuated globalization–but this was hard to find, and unlike our fight in the rural Midwest, the messenger rarely (if ever) looked or sounded like us, came from our communities, or shared our life experiences.

But, I’m not interested in complaining about this space, I want to transform it! There are many lessons from my organizing days with rural Indigenous communities that apply within the media policy landscape. We knew for example, that no matter how complex or multi-layered, globalization had always meant the loss of languages, cultures, traditional foods, values, ways of living, and knowledge. It’s also meant increased migration, urbanization, poverty and the homogenization of culture. We knew the media had historically been used as a tool of colonization and that our communities had suffered from inaccurate and incomplete representations of history. And we knew the migration of entire communities North was intimately connected to the threats traditional knowledge faced from media monopolies and other transnational conglomerates. Then as now, massive Free Trade agreements protected the patenting of life forms, funded GMOs, and monetized biopiracy—at the expense of our communities health and wellbeing.

As I enter a new program year at CMJ, I’ve been reflecting on how I can bring these two worlds closer together. While I love media policy, it’s fairly clear that our relationship to Free Trade and globalization is relatively uninspired in comparison to “Down, Down WTO!” And while I believe freedom of expression is necessary—I’m not convinced it takes precedent over a legacy struggle for self-determination.

At present I have more questions than answers, but it’s a start.

- How can we inspire action against AT&T or Verizon like we do with Cargill and Monsanto?

- How can biopiracy and genetic modification inform our approach to technology?

- What can a terminator seed teach us about locked phones?

- How can we get the FCC to be as widely known in justice circles as the WTO?

- What can the Global South teach beltway advocates about “Free, prior and informed consent?”

- How can we prioritize the rights of Indigenous Peoples and Traditional Knowledge when talking Intellectual Property Rights (IPR)?

- What can past experiences with the State Department, USAID, IMF and WTO teach us about how we engage with them on media and telcom?

- What did we learn from NAFTA, CAFTA and TRIPS and GAT that we can apply to TPP and ACTA?

No better time than the present.

As I write this, The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP)–a massive international trade pact pushed by the U.S. government at the behest of transnational corporations, is moving ahead. From July 2-10 leaders from the United States, Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, Malaysia, Vietnam, Brunei, Chile, and Peru, Japan, Mexico and Canada are gathering in San Diego, CA. The TPP is another secretive, multi-nation trade agreement that could extend restrictive intellectual property laws across the globe. In fact, it’s set to become the largest Free Trade Agreement in the world. Frightenly, a leaked version of the February 2011 draft U.S. TPP Intellectual Property Rights Chapter [PDF] suggests that U.S. negotiators are pushing for the adoption of copyright measures which are far more restrictive than currently required by international treaties including those that apply to traditional knowledge and cultural expression.

Earlier this year CMJ and MAG-Net joined the fight against SOPA and PIPA, and for nearly two years we have been actively engaged in the fight for Internet Freedom. Yet TPP (like NAFTA and the FTAA) threatens to undermine that struggle through secret plurilateral negotiations that trump the inroads we’ve made domestically. Our communities know what kind of Internet experience we want, and the healthy media and communications ecosystem we deserve. As with rural organizing, we should be addressing this issue at both ends of the spectrum, working for a common set of standards that improve the wellbeing of our communities of origin and the countries in which we live. Its not a terminator seed, but our vision is needed as much in the world of media and telcom trade as it is at the FCC or Public Utility Commissions. In fact, given our long legacy of transnational organizing, our voices are not only critical—our worldview is what will make the difference.

While there is a lot to unpack, there are two pieces I believe should be on the radar of the media justice community

1: Bio-Piracy and TPP’s intellectual property standards including corporate appropriation of natural biological materials, genes and traits, and the traditional knowledge of indigenous peoples.

2: Internet Freedom and the possibility that TPP may incorporate language that favors corporate interests, and which could result in enforcement action against Internet users

More to come, stay tuned.