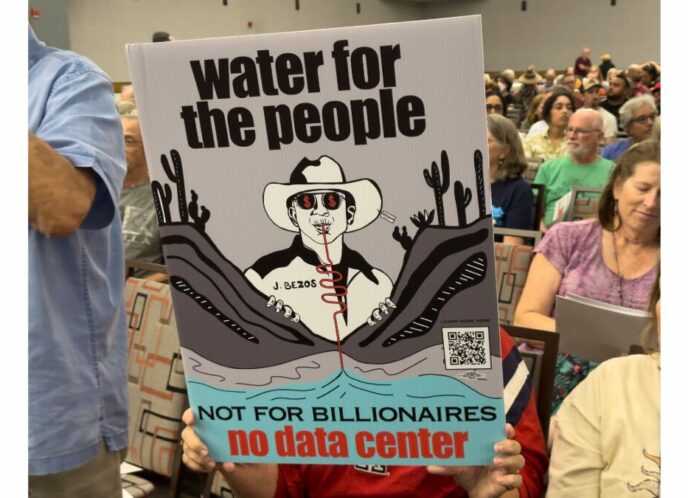

This year, the AMC started for me before I even set foot on the Wayne State University grounds. My partner, our friend and I pulled up to a charming red brick duplex in Detroit where our friend would be staying just a couple miles from campus down Woodward Avenue. The woman who opened up her home for our friend to stay is a community activist in town, and we all sat with each other for a while, discussing what was up in the city. She filled us in on the latest attack from the forces working to erode the social infrastructure of the longstanding Black and low-income communities: shutting off the water for over 150,000 residents who haven’t been able to keep up with their bills. The situation is still unfolding as I type, and this conversation set the tone for the rest of the trip.

This year, the AMC started for me before I even set foot on the Wayne State University grounds. My partner, our friend and I pulled up to a charming red brick duplex in Detroit where our friend would be staying just a couple miles from campus down Woodward Avenue. The woman who opened up her home for our friend to stay is a community activist in town, and we all sat with each other for a while, discussing what was up in the city. She filled us in on the latest attack from the forces working to erode the social infrastructure of the longstanding Black and low-income communities: shutting off the water for over 150,000 residents who haven’t been able to keep up with their bills. The situation is still unfolding as I type, and this conversation set the tone for the rest of the trip.

The main topics on my mind throughout the conference were historical context and visionary fiction: “How did we get here?” “Where are we going?”

The day before the conference began I attended the Racial Justice and Surveillance network gathering, which provided a great deal of insight for both of those questions. We heard from a local Black revolutionary about his experience with surveillance in the 1960’s. More broadly, the surveillance of communities of color, Indigenous communities and impoverished communities overall throughout U.S. history was a conversation topic for both small groups and full group discussions. Having lived in the Twin Cities for several years and learning about the surveillance of Native American communities and the American Indian Movement, this wasn’t necessarily new. But as a white man having a much less hostile relationship with surveillance and as a mediamaker, it provided space, time and stories to really think about my role in confronting racially motivated mass criminalization.

One big question to work through in small groups was “Is there a such thing as a sane surveillance program?”. The resounding answer was no, and then the question we dug into was, “What could community-led accountability structures to deal with conflict look like?” And if we had more time, we could have started to list out models that that already exist and work that is already happening.

At the end of the day we participated in a Peoples Movement Assembly and – amidst some tension and uneasiness in the room – we listed “White Supremacy [and a bunch of associated ism’s] is the root cause of surveillance” to the top of the gathering’s Points of Unity. While it was a challenging process for our multiracial group, I’m glad we were able to conclude with some consensus around an issue that so often remains below the surface.

With the conversations and lessons from the gathering grounding the rest of the conference, I also focused on the question of “how do we build the world we want?”

I re/learned the essential role that story plays in answering this question, quite movingly, in the workshop: Storytelling Black Women Writers’ Lives. A panel of Black women who have “dedicated their lives to unearthing the legacies of writers like Octavia Butler, Audre Lorde, June Jordan, and Lorraine Hansberry” invited attendees to ask them questions about anything they’re dealing with in their lives. The panelists, regarded as oracles, responded with insightful and enlightening stories from Black women as guidance. The impact was profound, and the future has been adjusted because of it.

The thread to the future continued as I discussed visionary fiction with some incredibly creative and radical writers, and how to produce short films that convey elements of the world we’d like to live in. It’s more clear every day that we need to operate at more of an imaginative level if we really want to transform our reality. Walidah Imarisha, co-editor of the forthcoming Octavia’s Brood anthology says it beautifully, “All organizing work is science fiction…What does a world without poverty look like? What does a world without prisons look like? What does a world with everyone having enough food and clothing look like? We don’t know. That’s science fiction. We believe that if we’re able to dream it and see it in our minds then we are much better able to move towards creating it.”

Leaving Detroit, these words and experiences have further inspired me to leap into the unknown through radical, time traveling storytelling – and create a world where communities can self-determine their relationship with water, and surveillance is an unbelievable fable from the past.

Erick Boustead is a Co-Director of MAG-Net Member Line Break Media, which exists to support people working for justice in their communities through narrative development and multimedia production and trainings.

Erick Boustead is a Co-Director of MAG-Net Member Line Break Media, which exists to support people working for justice in their communities through narrative development and multimedia production and trainings.