Reposted with permission from the Whitman Institute

The idea of restorative philanthropy was provoked for me at ivoh’s Restorative Narrative Colloquium last weekend. Restorative Narrative is an approach to storytelling (e.g. journalistic, documentary, etc.) that walks with a place or community over time, usually after a tragedy, to show how rebuilding and restoration are emerging. It contrasts (in both content and process) starkly to episodic, disaster-based storytelling that focuses only on the precise moment of tragedy (a shooting, a flood) then moves quickly on to the next.

I was particularly interested in the questions that were posed to media practitioners:

- Why am I choosing to tell this story now?

- Do I know enough about the tragedy/issue that occurred to tell the Restorative Narrative that emerged from it?

- Do I know enough about this story to tell it authentically?

- Have I told my sources about my Restorative Narrative approach to this story?

- How does this Restorative Narrative move the storyline from “what happened” to “what’s possible”?

- Have I acknowledged the “messy middle”?

- How am I defining “resilience” in this story?

- Am I trying too hard to fit this story into the Restorative Narrative framework?

- Do I have the support I need from my manager/editor?

- How am I feeling and reacting while reporting and telling this story?

- Have I been transparent about how telling this story could affect the people and communities involved?

It struck me that these questions could be shifted slightly for a funder/donor audience, to explore how restorative (vs. extractive or episodic) this investment might be. I re-imagine them as follows:

Why am I choosing to invest in this effort now?

Why us? Why now? Given the point of power in choice, it is vital to make transparent to us and partners what our intentions are.

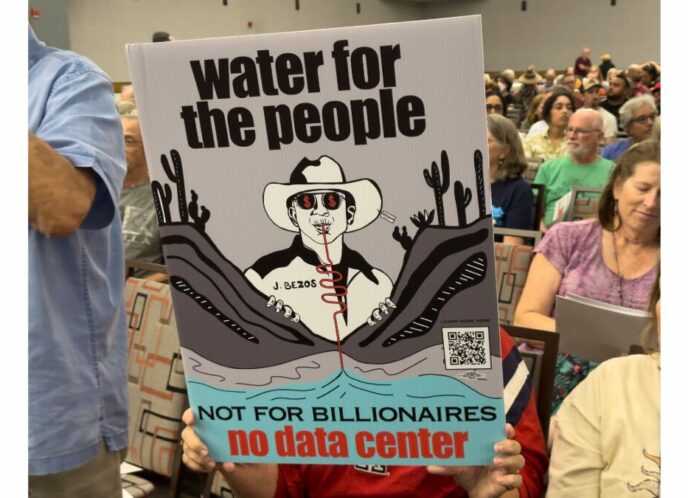

Do I know enough about the issue/community to make an investment that is restorative rather than extractive?

Philanthropy is often accused of being flashy trend followers, making sweeping shifts in focus and funding from year to year. Restorative support most certainly involves multi-year funding, support to build leader and organizational capacity, not “extracting” precious time for overly beaurocratic processes, and commitment to partner in a spirit of “we’re in this together.”

Do I know enough about this to invest authentically?

Not that we have to become “experts” in an issue, but it may help to get a strong sense of the landscape when we enter into new funding territory. Listening tours, and asking the leaders and funders who have been in the issue or region for much longer can be profoundly shape our thinking.

Have I engaged grantee/investee partners in my “restorative” approach to giving?

Speaking of what shapes our thinking, how am I engaging my grantee/investee partners in this process? Am I taking in their direct and sometimes indirect feedback about how to support this work, place, and people? Are they willing and interested in being the other half of my restorative approach? Are they true partners rather than subjects?

How does my investment move the focus from “what’s wrong” to “what’s possible”?

I’m reminded here of donation efforts that lead with pictures of “starving African children” while others lift up the creative, brilliant solutions being led by leaders like Africans in the Diaspora. Ultimately, it is the solidarity vs. charity approach being invoked here.

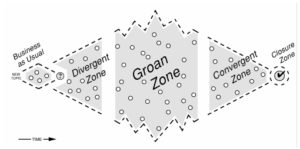

Have I acknowledged the “messy middle”?

This is by far my favorite question. The messy middle concept is a deep nod to “1 + 1 does not always = 2” in long term change work. The messy middle acknowledges that change takes time, that humans are complex, that change cannot be rushed, and to get through this we need relationships of trust and transparency.

In facilitator-speak, Sam Kaner called the messy middle of a dialogic process the “groan zone.” It’s that stretch in a group process between a divergent and convergent zone, where we’re past the point of no return and the group must land together in a new decision or approach. It’s often tiring and frustrating, but if the group can make into a convergent zone, oh the places we can go!

A grant-making that acknowledges the messy middle is one that stays less attached to uber specific outcomes and is more interested in long term relationships of mutual learning. It is, at root, a trust-based support, and one that encourages everyone involved to stick together through the “groan zones,” reflect on what is and isn’t working, and make sure to acknowledge every little bit of convergence and success that is achieved.

How am I defining “resilience” and “success” with this investment?

At TWI, we ask our grantee partners to help us understand what success looks like for them. This means we don’t impose our definition of success onto their work plan. We do, though, invite reflection periodically to look back at these definitions and benchmarks of success to listen into what our partners are learning and how their benchmarks are reached or morph over time.

Am I trying too hard?

I also love this question. It can be interpreted in so many ways. One that resonates with me is this – sometimes it’s just not the right time to make that grant/investment. The stars are not aligned, the institutions are not a good fit right now, and it is just OK to let it go and see if the possibility of partnership comes back around again. This question also maps to the notion of funder trend following – perhaps we are trying to hard to be part of a trend instead of fulfilling our mission and strategy?

Do I have the support I need from my board/trustees?

I’m learning that our boards need to be engaged and partnered with just as intentionally as our grantee partners. Are we including them in our evolving questions and learning about strategy? Are we ensuring that our trustees are connected to the leaders and work they are funding?

How am I feeling and reacting as I make this investment?

As stewards of resources, it is possible we downplay the role our feelings, preferences, and intuition play in our investing practice. At the Restorative Narrative colloquium, it was noted that the media practitioner telling the story is often healed, restored, and changed by telling the restorative story. As an investor, I wonder how that plays out? How are we being restored and fed by the grants and investments we make, particularly the long term partnerships?

Have I explored transparently with grantees/investees the how this investment could affect the people and communities involved?

I’m glad this list of questions ends with transparency. There is no replacement for honest brokering and being transparent and direct with our partners.

And we’ve come to the end of this particular set of questions, though I welcome more. What questions would you pose in an inquiry about restorative philanthropy? There are actually many efforts in philanthropy that appear to me to be restorative – particularly ones that invest deeply in place and people and long term solutions over time.

While there is no official movement (nor do we necessarily need one) that is currently dubbed “Restorative Philanthropy,” the question about whether our resources and giving processes are restorative rather than extractive or episodic is a powerful one. A question that I hope we who invest in social change pose to ourselves again and again.

Note: Big thanks to TWI partners Renaissance Journalism and ivoh for building and bringing us into the Restorative Narrative genre.