Ryan Grim contributed reporting / Reposted from Huffingtonpost.com

WASHINGTON — A month ago, Google lobbyist Katherine Oyama absorbed one of the more unusual congressional tongue-lashings in years when she appeared before a hearing of the House Judiciary Committee. Rep. Tom Marino (R-Pa.) joked that Oyama had walked into a "lion's den."

After praising representatives of drug giant Pfizer and the Motion Picture Association of America for their aggressive efforts to combat online piracy of American products, a bipartisan cadre of committee members spent much of the hearing berating Google, and Oyama personally, as corrupt, compromised and selfish.

"One of the companies represented here today has sought to obstruct the Committee's consideration of bipartisan legislation," House Judiciary Committee Chairman Lamar Smith (R-Texas) said.

"In my experience there's usually only one thing at stake when we have long lines outside a hearing as we do today, and when giant companies, like the ones opposing this bill, and their supporters start throwing around rhetoric like, 'This bill will kill the Internet,'" said Rep. Mel Watt (D-N.C.), glowering at Oyama. "That one thing is usually money."

It's not unheard-of for corporate representatives to pay public penance on Capitol Hill, but Google seemed a strange subject for abuse: Unlike recent corporate target MF Global and congressional villain Goldman Sachs, Google's shaming wasn't preceded by massive public outcry.

So what raised the committee's ire? An extremely technical, low-profile bill that isn't being covered by cable news, but has nearly 1,000 registered lobbyists officially working on it: the Stop Online Piracy Act, or SOPA — a bill with the power to fundamentally reshape the laws governing the Internet.

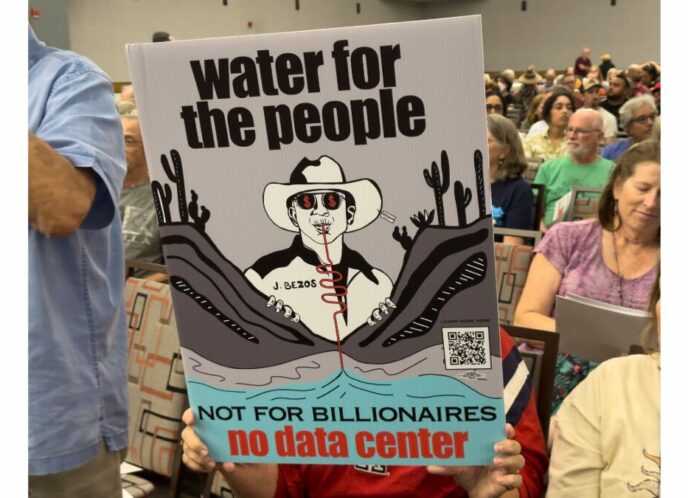

SOPA would imbue the federal government with broad powers to shut down whole web domains on the basis that it believes them to be associated with piracy — without a trial or even a traditional hearing. It would provide Hollywood with powerful new legal tools to stifle transactions with websites whose existence worries the movie industry.

The bill's supporters, which also include major record labels, trial lawyers and pharmaceutical giants, call SOPA a robust effort to curb piracy of American goods online.

Opponents, however, have castigated it as an unparalleled attack on free speech online. Civil liberties advocates say SOPA would give the U.S. government the same censorship tools used in China. Those in the technology sector warn that the bill creates enormous new barriers to entry for web startups, threatening innovation and job creation. Farther afield, librarians say that under the letter of the proposed anti-piracy law, they could be jailed for simply doing their jobs.

But with buy-in from powerful members of Congress on both sides of the aisle, SOPA's backers had hoped for few roadblocks en route to a Thursday committee vote and, from there, the House floor. The bill's future is in greater doubt, however, given unexpectedly strong opposition from both grassroots organizers and corporate players with a vested interest in maintaining the Internet's status quo.

In fact, SOPA and its companion Senate bill, Protect IP, have splintered the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the nation's preeminent business lobby. In October, Internet portal Yahoo publicly withdrew from the Chamber — an extremely rare move for a big U.S. business. Google lobbyists tell HuffPost they "wouldn't be surprised" if the leading search giant soon followed Yahoo out the door.

The opposition has succeeded in slowing legislative momentum. Sources in Congress and on K Street now say that Senate is unlikely to vote on its measure by the end of the year. And the bill's prospects become much slimmer in 2012, an election year in which members will spend much more time away from the Hill.

Yet in the meantime, other legislation has been left sitting idle, including bills to maintain current Medicare reimbursement rates for doctors, renew the payroll tax cut for the middle class and maintain the flow of unemployment benefits. So how has a bill this arcane occupied so much congressional attention?

Grassroots lobbying has been a factor, but the SOPA war in Congress has mostly been waged between different corporate elements, each with deep pockets. While bipartisanship has been hard to come by in Washington this year on high-profile issues, it's been easy to find on SOPA and the other corporate disputes that have taken much of the legislature's time this year — banks vs. retailers, Silicon Valley vs. Big Pharma. But unlike previous corporate spats on Capitol Hill, voters would quickly see the impact of the year's final congressional action if the government uses it to give their favorite websites the ax.

* * * * *

Movie studios, cable companies and major record labels have been railing against copied songs and films for decades. In the '20s, record labels required musicians to sign contracts promising never to appear on a new medium called "radio." Nearly a century later, the Recording Industry Association of America sued a 12-year old girl for downloading children's TV theme songs on her parents' computer. And for the past decade, they've hammered Capitol Hill with the same demand: Stop online piracy.

"Hollywood and the recording industry have a one-item agenda. You can't say to them, 'If you go softer on this, I'll give you that,' because there's no 'that' for them," says Gigi Sohn, president and Co-Founder of Public Knowledge, the leading nonprofit on Internet freedom issues, and a staunch opponent of SOPA.

The top target has been the Judiciary Committee, a powerful circle of lawmakers that is responsible not only for intellectual property rules, but judicial appointments, bankruptcy law and scores of issues involving constitutional rights.

In recent decades, the line between Hollywood and the Judiciary Committee has blurred. In the early 1990s, then Rep. Sonny Bono (R-Calif.), of Sonny & Cher, drafted a bill for the Judiciary Committee that extended the length of copyright protection by an additional 20 years. Bono's Southern California district was very close to Disneyland, and the copyrights on Disney's oldest Mickey Mouse cartoons were nearing their expiration. Bono's efforts ensured that Mickey's first appearance in "Steamboat Willie" would not enter the public domain until 2023.

Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Pat Leahy (D-Vt.) is Hollywood's current favorite son in Washington. His top two career campaign contributors are Time Warner and Disney, according to data compiled by Center for Responsive Politics; Time Warner has even given him cameo appearances in Batman movies, an experience Leahy talks of proudly.

Another committee member, Sen. Al Franken (D-Minn.), who has repeatedly called net neutrality "the most important free speech issue of our time," is a co-sponsor of the new anti-piracy legislation.

An aide to Franken says that the issue is personal: "He is … a copyright holder and he has worked with creatives and copyright holders." Franken has written several best-selling books, and was a longtime star of NBC's Saturday Night Live.

On the Republican side, former Judiciary Committee aides Allison Halataei and Lauren Pastarnack recently signed on as lobbyists for the entertainment industry, as Politico has reported.

According to an analysis by the Sunlight Foundation, a nonpartisan government transparency nonprofit, a full 16 former House Judiciary Committee staffers are now lobbying on intellectual property issues, with all but a handful pushing to enact SOPA.

In May Leahy introduced Protect IP, declaring that it "will protect the investment American companies make in developing brands and creating content and will protect the jobs associated with those investments."

The bill would give the Department of Justice the power to bring down foreign websites "dedicated to infringement" without going through the hassle of a trial — or even a traditional hearing. All DOJ has to do is convince a judge to approve the department's view that a site is in fact "primarily dedicated to infringement"; the law doesn't require the judge hear any defense from the website's operator.

Currently the government can only shut down domestic websites, and only if it plans to go to trial; taking down a website can only occur if a judge is shown probable cause that the site was used in the commission of a crime. The new bill doesn't require criminal activity for a takedown — only that the DOJ believes the site be "primarily dedicated to infringement."

Even with its existing powers, the government has improperly shuttered legitimate websites. In late 2010, Immigration and Customs Enforcement brought down dozens of websites with names like "boxedtvseries.com" and "dvdscollection.com." Most of those sites quickly moved their operations to identical sites with different domain names. But in the same sting, ICE also knocked out a handful of quite popular music blogs that artists frequently leaked songs to as a promotional tool.

On December 8, 2011, after more than a year, one of those websites, dajaz1.com, went back up. ICE, which declined to comment for this article, decided not to prosecute.

Under Leahy's bill, the government would have no obligation to ever even pretend to be proceeding toward a trial in order to keep a site suppressed indefinitely.

"Can the government be trusted to get this stuff right?" Asks Andrew Bridges, a lawyer with Fenwick & West who represented dajaz1.com throughout the proceeding. "I think the obvious answer is no. There's a reason why we have trials."

Leahy's bill would also empower corporations to demand that payment processors, advertisers and search engines stop doing business with sites the companies believe to be dedicated to infringement. A Hollywood studio could claim a website is "dedicated to infringement," and tell Google to stop registering the website in its search results. If Google protested, the company could haul Google into court.

This new set of corporate liabilities — known as a "private right of action" — prompted resistance from Wall Street. Both JPMorgan Chase, which operates a major global payment processing business, and the Financial Services Roundtable, a lobbying group representing the nation's biggest banks, began pressing Congress to reject the bill, arguing that it was unfair to hold banks accountable for the sins of others. Banks and payment processors didn't want to have Hollywood telling them who to do business with.

* * * * *

In 2010, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton blasted China's Internet censorship as an "information curtain."

But the way Protect IP tries to cut off foreign pirates' access to resources within the U.S. mimics many of the Chinese government's methods. Even former Sen. Chris Dodd (D-Conn.), now chairman of the Motion Picture Association of America, invoked China's methods when challenging Google's claim that it couldn't block access to specific websites on its search engine.

"When the Chinese told Google that they had to block sites or they couldn't do [business] in their country, they managed to figure out how to block sites," he told Variety.

The government's ability to shut down sites would involve federal tampering with the domestic Domain Name System — a basic Internet building block that links numerical addresses where Internet data is stored to alphabetical URL addresses that people actually type into web browsers. The Chinese government censors the Internet for its citizens by engaging in DNS blocking, restricting access to certain domains.

Tech experts warn that giving the U.S. government such powers could hinder the functionality of many web applications, severing the connection between domain URLs and numerical data addresses that many programs rely on. It would also hamper efforts to introduce a new security system known as DNSSEC, which national security programmers have been developing for years.

"The Act would allow the government to break the Internet addressing system," wrote 108 law professors in a July letter to Congress. "The Internet's Domain Name System ("DNS") is a foundational building block upon which the Internet has been built and on which its continued functioning critically depends. The Act will have potentially catastrophic consequences for the stability and security of the DNS."

Leahy's bill has whipped Internet advocacy groups into a frenzy. Dozens of nonprofits, including the Electronic Frontier Foundation and The Center for Democracy and Technology, issued strong statements condemning the bill. Fifty venture capitalists sent a letter to the Hill warning lawmakers that Leahy's bill could cripple tech startups with absurd legal fees prompted by Hollywood.

"Either they don't understand the basic fundamentals of the Internet," says Fred Wilson, referring to the broad congressional support for the bill, "or they're just doing this to get the MPAA and the [Recording Industry Association of America] off their backs." Wilson is managing partner with Union Square Ventures, the New York-based venture capital firm that seeded Twitter, among others.

By the fall, things would get much worse for tech companies. Amid intense lobbying pressure, the House would expand Leahy's bill, giving the U.S. Attorney General the power to shut down domestic websites without any intent to proceed to trial. Once that news became konwn, a slew of U.S. web companies, including Twitter, eBay and HuffPost parent company AOL, significantly ramped up lobbying efforts against the legislation.

But during the spring and early summer, the response from tech companies to Leahy's bill, though negative, was relatively muted. Most tech giants simply did not believe that such an extreme bill would ever really pass, according to lobbyists who worked against the legislation and staffers for Senators who oppose it. Leahy had introduced a previous Hollywood anti-piracy bill, known as COICA, in September 2010; that attempt had floundered for six months before he rewrote it as Protect IP. Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) responded to pressure from online activists by quickly putting a hold on Protect IP, preventing it from coming up for a vote indefinitely. Tech-friendly lawmaker Rep. Bob Goodlatte (R-Va.) was tasked with drawing up the House version, which Silicon Valley was assured would be far narrower in scope than Leahy's effort.

But over the summer, Hollywood ginned up support anywhere it could.

"Hollywood is really putting the screws to just about everybody they do business with. Netflix, the Writers Guild — they're all coming to me and saying, 'Can't you say something good about this?' " says Public Knowledge's Sohn.

Several unions associated with the entertainment industry endorsed the bill, including the Teamsters, a decidedly non-celebrity trucking union that works with Hollywood loading and transporting films and supplies. And since courts would ultimately have to decide what constitutes a site "dedicated to infringement," Leahy's bill would create a whole new realm of legal disputes, offering trial lawyers their own slice of the Internet.

The result was a perfect agglomeration of traditional Democratic Party constituencies, enabling Leahy to quickly round up 21 Democrats as co-sponsors — including some of the most progressive and Internet-friendly members of either chamber. Top members of the Democratic leadership, including Sens. Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) and Dick Durbin (D-Ill.), signed on alongside progressive stalwarts, like Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) and Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.), to the chagrin of Internet freedom groups who had once counted all of them as allies.

All 22 Democratic co-sponsors of Protect IP previously voted to protect net neutrality, a policy that prevents corporate telecommunications giants from dictating the accessibility and functionality of individual websites.

NBC Universal is one of multiple television behemoths lobbying in support of the bill, as is News Corp., the parent company for both Fox Pictures and Fox News. In the past six months, Fox News, Fox Business, MSNBC and CNBC have remained silent on Protect IP and SOPA, the house equivalent, according to a HuffPost review of cable TV records. Both Fox and NBC declined to comment for this article. News Corp. Chief Rupert Murdoch has personally lobbied Congress on Protect IP, meeting with Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) among others.

AOL Inc., HuffPost's parent company, is lobbying against the bill; CEO Tim Armstrong has personally met with President Obama.

* * * * *

While Washington has demonstrated little enthusiasm for taking substantive action on the jobs crisis, lawmakers always try to portray to whatever else they're working on as jobs-oriented. Obama heavily touted a Bush-negotiated free trade pact with Korea as a job-creator, though the government's own numbers on Korea imply a "negligible" impact on American jobs.

Even in inter-corporate fights, jobs remain the focus of every legislative pitch a lobbyist makes, and piracy provides a natural hook: stopping foreign websites from pirating U.S. goods would create American jobs!

The Motion Picture Association of America — a lobbying group for the dominant Hollywood studios — is pushing that line harder than anyone else in the fight. But amid epic unemployment, few voters are interested in prioritizing the complaints of silver-screen celebrities over the American middle class. So former Sen. Dodd, now the chairman of the MPAA, has embarked on an ambitious lobbying and PR campaign emphasizing the many less glamorous jobs involved in the film industry. During the last Congress Dodd moved more large and complex legislation through Congress than any Senator in modern memory, taking a lead role in the Wall Street overhaul and credit card reform, among other bills. If anybody can lead SOPA through this Congress, it's Dodd.

"Behind Hollywood's red-carpet image lays a blue-collar reality. Most of those 2.2 million jobs are held by middle income families and small-business owners, men and women whose names will never appear on a theater marquee, but whose efforts are critical," Dodd said in a Nov. 16 speech before the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce, the organization responsible for the "Hollywood Walk of Fame" honoring film and music celebrities.

Dodd's 2.2 million jobs figure, however, exaggerates Hollywood's contribution to the American economy. According to supplemental data provided to HuffPost by MPAA, only 272,000 people work for movie studios and television companies. The lobby group claims that an additional 430,000 people work in related "distribution" jobs dependent on Hollywood, legal web streamers like Netflix, the few remaining video store clerks and cashiers checking out DVD purchases.

Just how many of these "downstream" positions are really dependent on Hollywood is the subject of dispute among economists, and how many are hurt by kids downloading movies for free is even less clear. But the vast majority of the jobs Dodd & Co. claim are threatened by online piracy are only peripherally related to the entertainment business. MPAA takes credit for nearly 1.6 million jobs at florists, catering companies, hardware stores and other industries that work with major movie studios, assuming that these jobs could not ultimately be out of a job without Hollywood help.

"This is a joke," says economist Dean Baker, co-Director of the progressive-leaning Center for Economic and Policy Research. "This bill will have very little impact on jobs directly. And of course the money that people don't pay to the MPAA, they spend somewhere else. So this is about the distribution of jobs, not the number."

In July, the MPAA studios and a few entertainment unions launched Creative America, a site that purports to demonstrate the ravages of piracy on ordinary folks in the entertainment industry. The group is now engaged in an aggressive and expensive advertising campaign to promote Protect IP and SOPA as job-protecting legislation, claiming that pirates are "stealing … hundreds of thousands of American jobs."

WATCH the Creative America ad:

Dozens of other industries have lined up to support the bill, chanting the less-piracy-equals-more-jobs mantra. But like many talking points circulating around Capitol Hill, the sound bite hinges on a link between higher corporate profits and more jobs. For many of the firms in favor of the bill, that link is tenuous at best.

"If you're Nike, and you make tennis shoes and there's a company in some other country that can manufacture those for 10 cents on the dollar and sell them as if they were real Nikes, you have a big problem," says Christine Jones, General Counsel for Go Daddy, one of just two major tech companies to support the bill. Jones was a bundler for the 2008 presidential bid by Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.), raising as much as $100,000 for him. McCain, a Protect IP co-sponsor, denies any contact between himself and either Go Daddy or Jones.

But a large portion of Nike's labor force works overseas (often working in abusive labor conditions that the company has long vowed to end). Most of the firms lobbying on the legislation will not even publicly disclose the number of employees who actually work in the United States (Tiffany & Co., a supporter of the bill that does disclose, has 44 percent of their employees overseas).

But supporters of anti-piracy legislation continue to tout the jobs line. In a statement provided to HuffPost, Franken says the bill "an important jobs issue," insisting that, "The online sale of copyrighted content and counterfeit goods hurts American workers and businesses, and it ultimately means lost jobs."

Protect IP's support from liberals like Franken and traditional Democratic donors has not been lost among the conservative base. As the Tea Party Patriots proclaimed in an early autumn Facebook post:

"Have your own website? Maybe the government will shut it down tomorrow…without any notice to you. Republicans are going to introduce this in the House, Democrats in the Senate. WHAT??? Big Labor, Hollywood, U.S. Chamber of Commerce all in this together…against you."

During the years-long debate over net neutrality, Republicans repeatedly claimed that net neutrality rules amount to a "government takeover" of the Internet, insisting that the government doesn't need to and shouldn't "regulate the Internet."

"Here's what they wanna do: take the private Internet and put it all under government control," Tea Party favorite Rep. Marsha Blackburn (R-Tenn.) said in a web video uploaded to her own YouTube account in April. "Think about it. What's going to happen to the next Facebook innovator if they have to go apply with the government to get approval to develop a new application?"

And yet elected Republicans of all stripes, including Blackburn, whose district includes Nashville, are lining up to hail Protect IP and SOPA — accounting for 17 of 39 Senate co-sponsors and seven of nine House co-sponsors. Tea Party favorite Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.), whose state houses Universal Studios and Disney World, is a co-sponsor on the Senate side, while Reps. Mary Bono Mack (R-Calif.), Elton Gallegy (R-Calif.) and Dennis Ross (R-Fla.), who have heavy Hollywood presence in their districts, have signed on as co-sponsors in the House.

"This … is a huge giveaway to the trial lawyers, but the Republicans are all over this," says a frustrated Pedro Ribeiro, spokesman for Rep. Zoe Lofgren (D-Calif.), a lawmaker whose district is home to several Silicon Valley stalwarts and was one of the first members of Congress to speak out against the piracy bill.

* * * * *

With major corporate constituencies organizing on behalf of the bill, Silicon Valley stalwarts couldn't count on the U.S. Chamber of Commerce to air their complaints. In addition to Hollywood and Nike, pharmaceutical giants were making a big push.

Americans pay higher prescription drug prices than the citizens of any other nation, a product of strict intellectual property rules for prescription drugs. So many among the elderly and the uninsured import the same drugs at lower prices from Canada to avoid the sticker shock, a strategy advocated by both Consumer Reports

and AARP.

Though buying prescription drugs from Canada is technically illegal, the Food and Drug Administration has informally tolerated the purchases for years, provided the medicine is approved by prescription and is only for personal use. Several states have even adopted official Canadian drug importation regimes over the last decade, including Kansas under then-Gov. Kathleen Sebelieus, who now heads Obama's Department of Health and Human Services chief. Over one million Americans order drugs from pharmacies certified by the Canadian International Pharmacy Association,, a credentialing organization recommended by AARP for seniors to help ensure that a pharmacy in Canada is safe.

But major pharmaceutical companies hate this practice, which drains on their revenues, and the companies have deployed an aggressive campaign to associate legitimate Canadian drugs with the very real problem of Internet-purchased counterfeit medicines. (There are websites peddling bogus drugs who do their best to masquerade as legitimate Canadian pharmacies.)

"The major threat to patients in the U.S., however, is the Internet and the many professional-looking websites that promise safe, FDA-approved, branded medicines from countries such as Canada or the U.K.," Pfizer Chief Security Officer John Clark said at the Nov. 16 House hearing.

SOPA includes a host of provisions designed to crack down on counterfeit medicine that are written broadly enough to encumber the importation of safe medicine from legitimate Canadian pharmacies. Provisions that bar the importation of "mislabeled" drugs would block a great deal of unsafe pills from making their way to the U.S., but they would also block all Canadian prescription drugs, because Canada's drug warnings don't exactly match FDA warnings.

So while SOPA cosponsor Rep. Steve Chabot (R-Ohio) has few ties to unions or Hollywood, his second-biggest career campaign donor is Proctor & Gamble, a major drug company. The number two donor for Rep. Lee Terry (R-Neb.), another co-sponsor, is USA Drug, a southern drug store chain. Pharmaceutical giant Abbott Laboratories is the top 2012 donor for Protect IP co-sponsor Sen. Mike Enzi (R-Wy.), and 3 of the top 10 career donors for fellow co-sponsor Sen. Lindsay Graham (R-S.C.) are pharmaceutical companies.

With both Hollywood and the pharmaceutical industry backing the bill, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce threw it's full support behind the legislation, lobbying Congress directly. It also peddled its case to the public, starting up cuddly shell organizations to mask its own involvement. The Chamber set up The Coalition Against Counterfeiting and Piracy, which in turn established FightOnlineTheft.com. And FightOnlineTheft.com produced tear-jerker videos about the horrors of counterfeit medicine.

WATCH FightOnlineTheft.com's ad:

"Somebody could end up sick," reads a narrator, whose friend died after taking medicine purchased from Canada online. "Somebody could end up dead. It could be a child next time. It could be your friend, it could be anybody. And they just don't care. They are just after the money. And it has to be stopped."

* * * * *

By October, Smith, the House Judiciary Committee Chairman, who declined to comment for this article, stripped tech-friendly Rep. Goodlatte of responsibility for the House version of Protect IP, sparking panic among tech firms. Smith delivered for Hollywood, expanding Leahy's bill to give governments and corporations the power to bring down foreign and domestic websites alike, and broadening the definition of a condemnable site to anything that "infringes or facilitates infringement."

Courts will ultimately decide the meaning of that term, but if you believe SOPA-supporter Monster Cable, which keeps an extensive list of "blacklisted dealers" that sell "fake" Monster products, some of the biggest names in both the Internet and American retail could be targeted: eBay, Craigslist, Costco, Facebook, Sears and Twitpic. If SOPA passed, Monster, which makes high-priced versions of guitar cables and home electronic connectors, could demand that web hosting services take down not merely individual web pages selling allegedly bogus Monster cables at Sears.com, they could demand that the entire Sears website be taken down.

"The new law is touted as providing additional remedies for foreign sites, but it really strongly targets domestic players as well," says Bridges, the attorney for dajaz1.com, the site raided by ICE in 2010.

And the prospect of the government sacking entire websites because some user-generated content allegedly violates copyright laws creates tremendous free speech problems, civil liberties advocates say.

"Our primary concerns are with the fact that non-infringing content is going to be taken down in the process of taking down infringing content," says Michael MacLeod-Ball, First Amendment counsel for the American Civil Liberties Union. "The way the bill is set up, if a site has infringing content on it … their default reaction is going to be to take down the whole site."

While a judge has to review the Attorney General's request to take down a site, nobody from the site being targeted must be given a chance to defend themselves before the judge grants the AG's request. The AG doesn't ask a judge for a search warrant under SOPA, it requests to take down an entire website without a trial — or even a hearing.

Under current law, any U.S. website posting infringing content has to take the song or movie down at the request of whatever company owns the copyright. But under SOPA, companies could go directly to web hosting companies and require them to take down the entire website — not just individual songs and videos.

As a result, SOPA creates a new opening for corporate command of the Internet. Under SOPA, web hosting companies that take down legitimate websites at the behest of copyright holders would be granted blanket immunity from any liability for losses caused to those legitimate sites.

"Nobody's responsible," says University of Virginia Law School Professor Christopher Sprigman. "A website is taken down, there are robust First Amendment standards that should prevent it from being taken down, and it gets taken down anyway. Well whose responsible? No one."

That model could also pave the way for a new business model among hosting companies. Instead of waiting for Hollywood to ask that a site be shutdown, hosting companies could agree to monitor web traffic for them for a fee and preemptively take down infringing sites without having to be asked, Internet activists warn.

"It would be a very tragic thing if in the name of protecting artists, we saw the most important platform of our time become the province of just a few companies deciding what is and isn't legitimate expression," says Casey Rae-Hunter, deputy director of the Future of Music Coalition, an advocacy group for independent musicians that staunchly opposes Protect IP and SOPA, emphasizing that what is good for corporate record labels often doesn't translate into positive outcomes actual musicians.

Big companies targeted by Hollywood may be able to win copyright disputes in court. But for small startups, the implications are more dire. At worst, the bill would force productive startups to shut down in their nascent stages. At best, companies would have to hire additional legal staff to protect against the threat of a SOPA lawsuit.

Hollywood and the recording industry will "sue startups," says Patrick Ruffini, a Republican strategist and founder of Engage LLC, which is running PR against SOPA, "and if you get a $6 million or $7 million lawsuit slapped at you, it's very hard as a startup."

Twitter, for instance, could be required to remove any link on its platform to infringing content or face DNS annihilation, Internet activists have warned.

SOPA's supporters insist they aren't after Twitter or other prominent tech firms. But they also oppose narrowing the legislation to remove connotations for sites like Twitter.

"It's already hard enough to build a legitimate new business as it is, and this would make it much worse," says Dennis Yang, vice president of Infochimps, a company that provides specialty data-set search services. "What's really scary is we won't know which productive new businesses won't get off the ground, because MPAA used this bill to kill them before anybody heard about them."

While DNS blocking may well lead to the delisting of legitimate sites, web experts say it would be extremely unlikely to actually hamper piracy efforts that involve even moderate levels of sophistication. When the domain "illegalfreemovies.com" is taken down, site operators can take all of their information to "newillegalfreemovies.com." And tech developers are developing workarounds for domain seizures. A third-party developer has already introduced a program for Mozilla Firefox, the popular open-sourced web browser that allows its users to program their own add-on features, that forwards users from a domain that has been taken down to its newly-registered name.

The House bill also includes a host of provisions to expand the scope of what constitutes criminal copyright infringement at home, and would even make make it a felony to stream copyrighted videos online. The tactics are so extreme that American libraries are urging Congress to reject the bill on the grounds that librarians could be jailed for making good-faith judgments that their activities were within the law.

Libraries have always provided copyrighted material to the public for free. But in recent years, major lawsuits have been filed against libraries for streaming educational videos in university classes, allowing college students to access chapters of books electronically, and compiling a database of "orphan" books that are no longer in commercial circulation.

All of these activities have generally been protected by "fair use" — a legal doctrine that allows for free distribution of copyrighted information under a variety of circumstances, especially for educational use. But "fair use" standards have changed over time, from lawsuit to lawsuit. And with movie studios and publishing houses challenging the meaning of fair use under digital methods of distribution, a librarian who copies a DVD to the library's database and streams it in the library could find herself charged with a felony under SOPA.

"It's just freaky for libraries to find themselves in this kind of situation, because we're nonprofit, small-potatoes actors," Brandon Butler, Director of Public Policy Initiatives for the Association of Research Libraries, tells HuffPost.

* * * * *

In October, the Chamber continued to support Protect IP as indications mounted that the House version would not moderate the Senate bill, but instead launch a still more-aggressive assault on the Internet's infrastructure. By mid-month, Yahoo! had had enough — it left the Chamber outright. No corporation had publicly left the Chamber since 2009, when Apple departed after the lobby shop officially opposed climate change legislation, siding with oil companies while peddling science-denialist talking points.

Google could leave the Chamber any day now, but unlike Yahoo!, Google is deeply involved in the Chamber's effort to allow American companies to bring money stashed offshore back to the U.S. at a greatly reduced or nonexistent tax rate. A tax holiday could save Google significant change: The company saves about $1 billion a year by pushing its profits to Ireland and the Netherlands, Bloomberg reported, but it only avoids paying U.S. taxes on that money so long as it never brings the money back to the states.

Leaving the Chamber would mean bearing the full brunt of the PR blow for its lobbying, as Google would no longer be able to shield its activity behind Chamber coalitions.

Since Leahy proposed similar legislation in late 2010, Google has been the most high-profile corporate opponent of the anti-piracy legislation. The company's business model depends on an open Internet, and some of its top properties, particularly YouTube, have long been targets for Hollywood and TV moguls.

Having a corporate ally is a clear boost for libraries, free speech advocates and open-Internet nonprofits, who don't have the lobbying might Google has.

But of all the corporate sponsors to have in Washington right now, Google is probably the least helpful. The Internal Revenue Service is investigating the company's tax maneuvering; the Department of Justice is reviewing its acquisition of Motorola Mobility; the Federal Trade Commission and a Senate panel are investigating whether its search tactics constitute an illegal monopoly.

But nothing has been more damaging on SOPA than Google's run-in with online pharmacies.

In August, Google paid $500 million to settle charges from the U.S. Department of Justice that it accepted ads from pharmacies that shipped drugs to American consumers in violation of American law. Many of these were violations that the government frequently tolerates, but by blatantly and repeatedly allowing ads from pharmacies that sell prescription drugs without a prescription, DOJ decided to take action.

"Google's been great on this, but their reputation has been systematically trashed in Washington by their opponents," says Aaron Swartz, co-founder of Reddit, whose group Demand Progress was an early Protect IP opponent, and which now boasts of organizing over 600,000 people to oppose it.

Roughly a week after the House bill dropped at the end of October, nine tech giants — including Google, Facebook, Twitter, eBay, and HuffPost's parent company, AOL Inc. — sent a letter to lawmakers urging them to reject the bill.

But on Capitol Hill, Google's name was the one that mattered. Things got especially ugly during the House hearing featuring Google's Oyama, a week after the letter was sent. Of the nine tech companies, only Google was invited to appear before the Judiciary Committee — against five SOPA supporters. Lawmakers didn't hide their hostility.

"Google just settled a federal criminal investigation into the company's active promotion of rogue websites that pushed illegal prescription and counterfeit drugs on American consumers," Smith said at the hearing. "Given Google's record, their objection to authorizing a court to order a search engine to not steer consumers to foreign rogue sites is more easily understood."

On the Senate side, Google doesn't even have the backing of one of its own Senator, Democrat Dianne Feinstein. When HuffPost asked Feinstein, a Protect IP co-sponsor, if it was difficult for her to navigate the bill with Silicon Valley and Hollywood on opposite sides, she responded: "I don't believe that they are. I thought we had reconciled the issues. The bill's been passed out of committee." The response seems incredible given the outcry from Silicon Valley, and Google in particular, but the complexity of the legislation has left many lawmakers vulnerable to K Street spin.

Tech companies had also lost Wall Street as a key ally; by this fall, the baggage of earlier lobbying campaigns weighed heavily on the banks. During the first six months of 2011, banks worked Congress hard on debit card swipe fees, pressuring just about every member of the Senate to buck loyal campaign contributors in the American retail industry. The banks ultimately lost in Congress, but not before winning over several reluctant lawmakers. Persuasion came with a high price: Banks take a reputation hit every time they're in the news lobbying.

So for the time being, Wall Street is shying away from obvious feuds with other companies.

"Nobody likes this private right of action," says Peter Freeman, a lobbyist with the Financial Services Roundtable. "But we're focused on other things right now."

* * * * *

Never underestimate the ability of venture capitalists, who invest in new, job-creating companies, to charm Congress.

This fall, when it became clear that the House bill would cause havoc for tech companies, a handful of tech-friendly VCs, including Twitter-investor Union Square, sent a letter to Congress and flew to Washington to meet with lawmakers.

Rep. Darrell Issa (R-Calif.), chair of the powerful House Oversight and Government Reform Committee and an aggressive partisan whose top career campaign contributors include SOPA supporters AT&T and Microsoft, was particularly attentive to the substance of the issues involved, according to VC representatives who met with his office.

In December, Issa, a business owner himself, joined a small bipartisan group of lawmakers in proposing an alternative to the Leahy/Smith legislation. Issa jumped in with Sen. Wyden, who chairs the Senate subcommittee on international trade, and Sen. Mark Warner (D-Va.), a former venture capitalist who helped seed telecom company Nextel and a host of Internet companies.

"I got a company, Rosetta Stone, who gets pirated on a regular basis — you've gotta have accountability around that," says Warner, referring to the language-learning software company with offices in Arlington and Harrisonburg, Va. "But … I think the approach Senator Wyden has been working will strike a better balance."

The alternative legislation would drop all of SOPA's efforts against domestic websites, and would not allow the DOJ to engage in DNS blocking.

It would also kick arbitration of any foreign infringement claims to the U.S. International Trade Commission, which already handles issues of foreign piracy as a policy issue. After a formal public hearing, ITC would be empowered to regulate rogue infringing websites as unfair imports — permitting ITC to cutoff any U.S. payment processors or advertisers from doing business with such sites, denying them access to American money and financial infrastructure.

It's not clear how much support the Wyden-Issa bill can secure: The Chamber declined to comment on it. But those backing the alternative don't have to actually pass their version to stall SOPA.

"There really is a worthwhile strategy in delay," says Tim Karr, campaign director for Free Press, a media reform nonprofit.

And the potential of SOPA passing in January has already sparked a new round of corporate interest in the legislation, forcing companies on both sides of the issue to throw money at any lawmaker who signals ambivalence on the issue.

Sen. Joe Lieberman (I-Conn.), a Protect IP co-sponsor, has suggested he's willing to jump ship. "I've been trying to gauge the concerns," Lieberman tells HuffPost.

The White House is intensely divided over SOPA and Protect IP, according to administration sources, and hasn't issued any statement on them — suggesting the President won't be pushing piracy legislation as hard as he did for free-trade and the patent-reform legislation. And opponents of Protect IP and SOPA have the dysfunctionality of Congress at their backs. Next year is an election year, and congressional leadership will not want to force an issue that divides campaign donors anywhere near November.

It's a strategy that has worked before. In 2006, Congress pressed for legislation to give telecom giants the capacity to dictate traffic volumes to individual websites. Billions of dollars a year in corporate profits were at stake, and the bill had bipartisan support. But the legislation died, quietly, over several years.

"By pushing it off and pushing it off, we eventually killed it," says Adam Green, co-founder of the Progressive Change Campaign Committee, a long-time net neutrality defender.

This year's legislative tussles over corporate profits have been only tangentially related to the ordinary lives of American citizens — they've essentially been about hidden fees. The price of the patent fight and debit swipe fees are reflected in more expensive consumer goods, but citizens don't see how much of that price tag results from a corporate dispute over intellectual property or merchant card charges.

But everyone uses the Internet. While many of SOPA's consequences would be hidden from public view in out-of-court negotiations, some effects will be felt directly. The intensely personal nature of Internet use has elevated this particular intra-corporate squabble to something the broader public is beginning to pay attention to.

"Congress is on the verge of wrecking the greatest engine of innovation and greatest platform for democracy ever known to human kind," says David Segal, Executive Director of Demand Progress. "And for what? For the sake of propping up an ossified industry that refuses to change with the times, but happens to make a lot of campaign contributions."

This article has been updated to reflect the involvement of entertainment unions in Creative America.