By Betty Yu

Today, national Media Action Grassroots Network (MAG-Net) member, Native Public Media (NPM) hosts the first ever Tribal Telecom conference in Tucson, Arizona. At the conference tribal leaders, government officials and entrepreneurs are coming together to share information, explore options, and pursue solutions to advance close the digital divide for tribal communities.

On January 25th, last week, Traci Morris of NPM was a special guest on MAG-Net’s monthly digital dialogue call, Beyond Access: Owning Community Broadband Networks. “By any measure, communities on tribal lands have less access to community broadband than any other segment of the population”, Traci remarks, “Only six tribes in Indian country got BTOP broadband funding last year – this doesn't do enough to bridge the digital divide”. Traci provided a sobering overview of the state of communications access in Indian country, citing that only 68% of people actually have telephone access and that only less than 10 percent of have broadband access.” Traci continued to assert the Internet is an equalizer and how it’s key for economic development, and community growth opportunities, providing Native Americans with access to health care, jobs and more.

The MAG-Net Dialogue also featured Christopher Mitchell of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance’s (ILSR) New Rules project, an organization devoted to providing news, information, research, and connections to the nation-wide movement of building broadband networks that are directly accountable to the community they serve. ILSR encourages community ownership of structures such as public ownership, cooperative models, and other nonprofit approaches.

Benefits of Community Broadband Networks

Just like electricity, broadband is now a basic element of necessary infrastructure that must be guaranteed by policy and investment in order to ensure our nation’s economic survival. In 2010, The FCC reported that between 14 and 24 million Americans lack access to broadband and found that unserved areas are disproportionately rural or low-income. A 2010 Pew Center study found that while 66% of all adults now have broadband at home, just 56% of African Americans, 66% of Latinos and 45% of those making less than $30,000 a year do.

Community broadband networks empower communities to make creative choices on how broadband infrastructure deployment and service provision can best serve their social and economic development needs. In the best and most common examples, a community might decide to use wireless technologies to extend services to hard-to-reach areas. Community networks create opportunities that retain talent and business and allow for sustainable economic growth. These models present new and innovative opportunities to extend services and prove the viability of underserved and unserved communities by changing the cost structure of the investment model.

Local owned infrastructures allow communities to build to suit local needs, geographic strengths and bottlenecks in ways that can greatly reduce cost. Communities that have invested in these networks have seen tremendous benefits. Even small communities have generated millions of dollars in cumulative savings from reduced rates – caused by competition. According to major employers have cited broadband networks as a deciding factor in choosing a new site and existing businesses have prospered in a more competitive environment.

Telecoms Pose Challenges and Threats

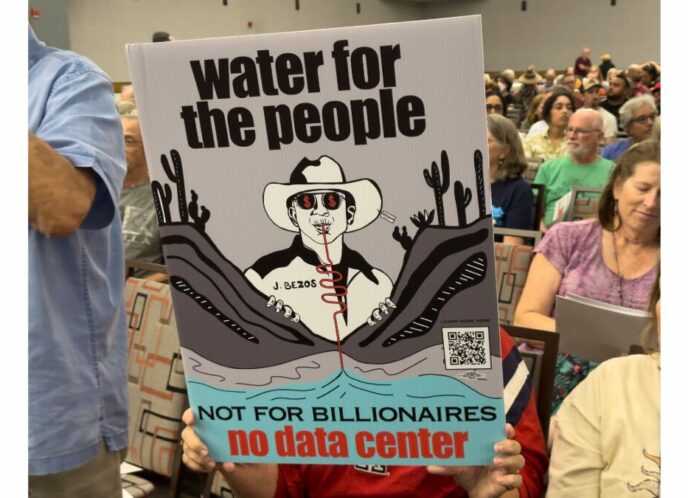

The continued monopolization of broadband wire infrastructure by a few large incumbents creates a powerful force aimed at protecting the current business model—one that leads to digital redlining, exclusion of communities of color, and higher costs and lower speeds for all subscribers. There are 18 states that have legislation that either bans community networks

For many years, telecommunication and cable companies have been lobbying hard on the state level to push legislation that would prevent municipal broadband networks. Most recently, last week AT&T reignited their push to pass a bill in the state legislature that “will gut the self-determination of local communities in the digital age”, according to Mitchell. “The market power of AT&T and Time Warner Cable has already driven most private sector competition from the market — now they want to use their lobbying clout to ensure that the communities themselves cannot build the networks they need to attract economic development and maintain a high quality of life.”

Despite these threats, local communities are finding innovate ways to pool resources together to start their own broadband networks. The MAG-Net digital dialogue also featured Danielle Chynoweth, co-founder of Urbana-‐Champaign Independent Media Center (UCIMC) who transformed their organization into an instrumental leader in winning a $22.5 million in Broadband infrastructure funds for their mainly rural community – a community of about 120,000 with a large research one university in a community still divided by race and class.

“Much of our community had no high speed option through the private sector as AT&T has cherry picked where to deliver UVerse high speed Internet. Winning the broadband funds was the capstone on a decade of local organizing around digital inclusion.”, Danielle continues to explain, “UCIMC has long sponsored the development of open source community wireless systems and deployed the first wifi network in Urbana, extended in collaboration with the city. Our system was used as well by townships in South Africa as tribal lands out west.”

UCIMC members helped to spearhead the creation of a Broadband Access committee of the local cable and telecommunication commission. During the grants process, Urbana IMC used these funds to get stimulus funds.

Chris Mitchell applauded the successful national fight to win the Local Community Radio Act in December 2010 and the need to study and learn how that battle was won. This win now allows communities to own their own community media infrastructure through operating their own lower power radio stations. Lessons can be learned from this 10-year fight as communities pursue owning their own broadband infrastructure.

###

Betty is the National Organizer for the Media Action Grassroots Network (MAG-Net) where she manages our national media justice network of over 130 grassroots community organizations, coordinates regional chapters and curates the media justice learning community.