This article was originally published on Truth Out, it has been reposted with their permission.

During the month of April, at least 100 of those incarcerated at Stateville Correctional Center, about an hour outside of Chicago, Illinois, participated in a boycott of the overpriced phone calls, commissary goods and vending machines. “Mass incarceration is a luxury business,” stated Patrick Pursley, one of the men who joined in the boycott.

The boycott comes at a time of growing demonstrations led by those inside US prisons. The most successful in recent memory was a series of hunger strikes at California’s Pelican Bay State Prison, organized by those protesting solitary confinement in the security housing unit (SHU), beginning with one in 2011, and another in 2013 that spread across the state involving 30,000 people inside 24 different prisons, including women in the Central California Women’s Facility. The largest hunger strike in the history of the US, it lasted for two months and was only suspended when a judge agreed to force-feed those who remained on strike.

Since then, there appears to be an uptick in actions on the other side of the walls. In early June, at least seven people in Waupun Correctional Institution, located in central Wisconsin, organized a hunger strike to protest the conditions of solitary confinement and lack of resources for those with mental health issues.

In Alabama, a series of work stoppages were recently coordinated to protest overcrowding, poor conditions and unpaid prison labor, what those involved say amounts to slavery. The Free Alabama Movement held a 10-day strike beginning May 1, 2016. A national work stoppage has been called for September 9, and a statement released proclaims, “We will not only demand the end to prison slavery, we will end it ourselves by ceasing to be slaves.”

At a privately run immigration detention center in Karnes, Texas, 78 women initiated a hunger strike in April 2015, to draw attention to the inadequate treatment of them and their children. They released an open letter explaining their intentions, writing, “We came to this country with our children looking for help and refuge, and we’re being treated like criminals … We deserve to be treated with dignity and to be respected.”

While these actions have been short-lived, and most often only involved small numbers of people, they are not insignificant. These are signs of a rising spirit of resistance that has not been seen since the Attica rebellion in 1971, when 1,000 incarcerated men took over the New York prison demanding better conditions. Several have put a spotlight on the widespread use of solitary confinement, while others have targeted the prison industrial complex and the private companies that make millions off of a captive population.

Who Pays?

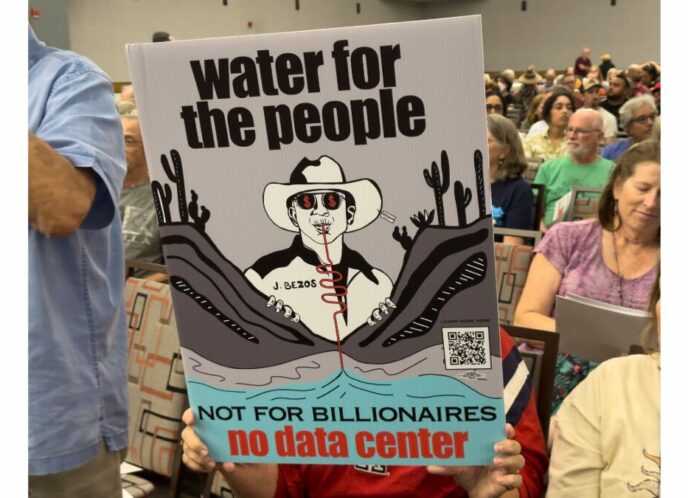

In Illinois, the cost of incarceration has been highlighted by the recent boycott at Stateville. Here in the “Land of Lincoln,” phone calls from prison are among the most expensive in the country. About $13 million a year is paid out in “commissions” by the provider, Securus Technologies, to the Illinois Department of Corrections (IDOC), what is effectively a kickback for the rights to an exclusive contract. This is the highest dollar amount of any state in the US. Kickbacks are one of the primary reasons driving the high cost of these phone calls.

Many may think that those behind bars are the ones who pay the cost of a phone call from prison, but it is most often their family members. The boycott was organized, as Patrick Pursley told Truthout, because incarceration is “too expensive on families.” According to the report “Who Pays?: The True Cost of Incarceration on Families,” released by the Ella Baker Center, one-third of families claimed they went into debt to pay for phone calls and visitations.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has recently stepped in to regulate the entire prison phone industry. On October 22, 2015, the FCC passed new rules for all prisons and jails, said Commissioner Mignon Clyburn, who has championed the issue, in a prepared statement, “States must do their part and take a hard look at their site commission practices and how such payments impact prices, service and the reverberating impact on the community.”

Illinois is the first state in the country where legislation has been advanced in the wake of the FCC’s decision. A bill, HB6200, sponsored by Carol Ammons (D-Urbana), has sailed through the Illinois legislature and is headed to Gov. Bruce Rauner for an expected signature. If passed, a four dollar phone call will be cut in half.

Wandjell Harvey-Robinson, of Champaign, Illinois, was in third grade when her parents were incarcerated, and at times could not afford to talk to them over the phone. “No child should ever feel like their love for their family is too expensive,” she said at a press conference.

Vigil for True Justice

Opened in 1925, Stateville was built in a “roundhouse” design with cells in a circle, and a tower in the center with guards constantly watching. It is modelled after Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon, what French philosopher Michel Foucault called in his book Discipline and Punish the prototype for modern state surveillance. Originally built for 1,500, today Stateville holds 3,500 people.

Joseph Dole, who is incarcerated at Stateville and was involved in the recent boycott, told Truthout the boycott was inspired by past actions at Stateville, and elsewhere in Illinois. Dole is a self-professed jailhouse lawyer and incarcerated writer. He was previously held at the notorious Tamms Correctional Center where everyone endured solitary confinement. When it was closed in 2013, after a campaign by the Tamms Year Ten Coalition (which included several incarcerated activists), Dole was moved to Stateville. He is author of A Costly American Hatred, a rare perspective on mass incarceration from the inside.

Dole had read in Stateville Speaks, a newsletter written by people who are incarcerated, about an action in April 2012 called the “Vigil for True Justice.” Copies of Stateville Speaks archived online include a March 2012 issue that published an announcement of the upcoming vigil. It called for a 30-day moratorium beginning April 1 from “using prison phone systems and making vending machine and unnecessary prison commissary purchases.” It advised those who participated to “keep your money in your pocket.”

Dole and others had also heard about the hunger strike carried out by those inside Menard Correctional Center, located in southern Illinois. “Those guys have got real solidarity,” Dole stated admiringly. When Tamms was closed, people held there were moved to other institutions across Illinois. Many were thrown into isolation cells without administrative hearings. Those sent to Menard’s High Security Unit organized a month-long hunger strike in early 2014. Their demands were modeled after those put out by the Pelican Bay protesters.

There are frequently smaller protests that are quickly squashed, but news of them eventually travels. “Some things fly through the grapevine,” Dole said, “sometimes you won’t hear about it until much later.”

Bilked Out of Millions

Growing frustration over the phone system prompted the boycott at Stateville this past April. The phones are maintained by Securus Technologies, one of the two industry leaders, and what James Kilgore and I have called a “carceral conglomerate.”

As Dole recounted, just before the boycott, “Securus had started cutting in on our phone calls with a threatening message.” Typically an automated voice will come on at the beginning of a conversation, warning against the use of three-way calls which are prohibited, but these interruptions had become more repeated. They were aggravating when people were trying to discuss personal matters. Dole said he and about a dozen others filed complaints with the FCC, and after about three weeks the messages mysteriously stopped.

Dole also complained that his mother had lost money after Securus suspended her account. When she asked what happened, she was told her account was closed to “protect her.” She then could never get her money refunded.

The plan was to boycott the phones beginning April 1, but the idea soon spread to include the vending machines and commissary store, which provides everyday items like deodorant, aspirin, and socks — for a steep fee, of course.

On April 4, the first Monday of the month, Dole said that about two-thirds of the guys from three galleries, with about 50-60 on each gallery, refused to go to the commissary store. Dole has written in the past about how those incarcerated in Illinois are “bilked” out of millions of dollars from purchasing commissary items.

According to Pursley, it can cost $6 for a sandwich, or $8 for a “handful” of vegetables. “Families are largely poor,” he explained, “prison jobs are rare, and they may only pay $25 a month.” He accused the IDOC of violating state law.

The Illinois Department of Corrections is allowed to charge an additional 25 percent above the cost for commissary goods, plus a 7 percent surcharge fee. The IDOC also collects a 50 percent commission on the everyday items purchased at the commissary store. The amount taken in is not disclosed by the department, but the figure is surely in the millions. In 2013, there was $30 million deposited into 523 Fund, which was made up from commissions from phone calls, commissary as well as federal funds. Said to “benefit inmates,” the money is used to cover general expenses like medical treatment and law libraries, as well as pay for guard salaries.

Lockdown

When prison officials found out, Pursley said, they “interrupted and disrupted.” A lockdown was immediately imposed. Everyone from the three galleries was interrogated by internal affairs about the boycott.

Dole was called into an office and questioned whether he was involved. “Hell yes,” he told them. The officers tried to intimidate him, “You know what can happen if you participate.” Dole responded, “You can’t force my family to use these services.”

Dole said he was one of the “very few” who sustained the boycott the entire month. “The guys have no backbone,” he said.

“The boycott crumbled,” said Pursley. “It started strong but fell apart, except for the five percent who held strong all month.” Many were understandably fearful of the administration and unwilling to take a stand.

I spoke about these demonstrations with Gregory Koger, who refused food in solidarity with the Pelican Bay hunger strike in the summer of 2014 while in Cook County jail for videotaping a protest, and previously served eleven years in Illinois prisons. He saw many smaller demonstrations, but said they would eventually dissipate. “What’s most important is that people have support from the outside world,” he told me. “Without that, these demonstrations are easily squashed.”

As more actions are organized by those on the inside, they will surely be met with increased repression by the authorities. The planned actions in Alabama in September will test the resolve of those on the inside. What remains to be seen is whether those on the outside will meet incarcerated activists’ calls to action with the same amount of commitment.