This piece featured at Truthout by Brian Dolinar features the work of MAG-Net anchors Generation Justice, Voices for Racial Justice, and Urbana-Chamaign Independent Media Center in bringing the voices of children with incarcerated parents before the FCC in its recent regulation of the prison phone industry.

Earlier in October, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) voted at its monthly meeting to cap the rates of phone calls from prisons and jails after years of profiteering by telecommunications companies that have made millions off of incarcerated people and their families. In her comments before the vote, FCC Commissioner Mignon Clyburn, who has long championed this issue, recognized in the audience Kevin Reese Jr., a 12-year-old whose father is incarcerated. “The reason we are doing this is because we care about your future,” said Clyburn, her voice trembling. “The reason we are here today is because you deserve relief.”

Earlier in October, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) voted at its monthly meeting to cap the rates of phone calls from prisons and jails after years of profiteering by telecommunications companies that have made millions off of incarcerated people and their families. In her comments before the vote, FCC Commissioner Mignon Clyburn, who has long championed this issue, recognized in the audience Kevin Reese Jr., a 12-year-old whose father is incarcerated. “The reason we are doing this is because we care about your future,” said Clyburn, her voice trembling. “The reason we are here today is because you deserve relief.”

Kevin Reese traveled to Washington, DC, for the first time with his mother along with a delegation attending the FCC hearing. Since he was just a baby, his father has been incarcerated at Lino Lakes Correctional Facility in Minnesota, which has thehighest rates for phone calls in the country. As Kevin was growing up, the phone was the way he stayed in touch with his father. “If I wasn’t able to talk to him,” he says in a video made for the campaign, “I wouldn’t know my dad. Everyone should have a dad.” Now that the FCC has lowered rates, “It’ll be better, just knowing I can talk to him every day.”

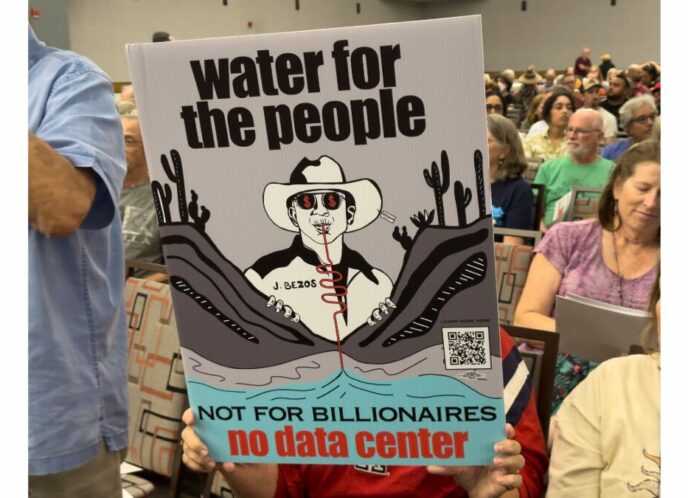

Under the umbrella of the Campaign for Prison Phone Justice, this effort has been led by the Human Rights Defense Center, Center for Media Justice and Working Narratives. It has involved pro bono attorneys, policy experts, lawmakers, media activists and civil rights organizations. A letter by the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights sent to the FCC before its vote was signed by a wide array of organizations including the NAACP, Urban League, American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and National Organization for Women.

What was once a $6 call will now be only $1.65.

In this campaign, the Media Action Grassroots Network (MAG-Net), a national coalition of social justice organizations including, among others, Voices for Racial Justice, Generation Justice and the Urbana-Champaign Independent Media Center, played a critical role in advancing the voices of those impacted, particularly children like Kevin Reese.

There are an estimated 2.7 million children with an incarcerated parent in the United States. As their stories remind us, a child doesn’t stop loving a parent when they go to prison. For a son or a daughter, regular phone calls are a lifeline to a parent. MAG-Net sent a delegation including children with incarcerated parents to advocate before lawmakers and attend the FCC’s final ruling. Truthout spoke with some of the organizations working with them to find out their strategies of spotlighting the lives of those who for too long have remained in the shadows.

Building Power

Activists today have organized around the hashtag #PhoneJustice, but the campaign goes back to a time before Twitter when the internet was still young. Throughout the campaign, those people most affected have taken the lead. In 2000, Martha Wrightfiled a lawsuit seeking legal remedy to the high cost of phone calls she was paying to talk to her grandson locked up in a federal penitentiary. Although passing away earlier this year, Wright was also acknowledged on the floor by Commissioner Clyburn.

The case was eventually referred to the FCC, which two years ago took its first step of capping rates for interstate calls. On October 22, 2015, the commission approved itssecond ruling, which will bring sweeping reform of the industry. Rates are capped at a maximum fee of 11 cents per minute for state and federal prisons. In large jails with a population of more than 1,000, which account for approximately 85 percent of those in jail on any given day, calls will be capped at 14 cents per minute. For smaller jails, which sheriffs argued bear greater expense, calls will be no more than 22 cents per minute. The rates will go into effect in 2016. For Kevin Reese, what was once a $6 call to talk to his dad, will now be only $1.65.

“The people who are most directly impacted should be the people making the decisions about how their story gets told.”

The 12-year-old got involved in the phone justice campaign through his father, Kevin Reese Sr., who is an activist from inside prison and works with the group Voices for Racial Justice, based in Minneapolis. Two years ago, the older Reese heard Vina Kay, executive director for the organization, on the radio talking about the prison phone justice campaign. He wrote her a letter, they began a correspondence and together they organized a one-day workshop in the prison. Soon, Kay was introduced to Reese Sr.’s family, including his son. Young Kevin was shy at first, but soon warmed up. Kay took him with her own family to see the movie Selma.

In September, after Kevin Reese Sr. gathered 100 letters about restoring voting rights for those released from prison, his son personally delivered them to Minnesota Gov. Mark Dayton. In just a short time, young Kevin was able to connect with the governor. In an interview with Truthout, Kay said he was able to “humanize incarceration for families, and for children in particular.” When it came time to send a representative to lobby the FCC, Kevin immediately came to mind. He was featured in several media stories about the FCC’s decision on prison phone calls, including anNBC report.

The goal of Voices for Racial Justice, Kay told Truthout, was “building power” and creating a space to elevate the voices of kids like Kevin. Especially when working with people of color, it is important they don’t feel used, but that they have a sense of agency.

“I’ll Stand Up for Him”

Jazlin Mendoza was another young person whose story was mentioned by Commissioner Clyburn as she moved to vote for reforms. Clyburn described Jazlin’s family forgoing a computer for college in order to pay for the phone calls to her father in a federal penitentiary. Jazlin, now 21, has grown up while her father has been in prison for the past 12 years.

In a video produced by Generation Justice, a youth media project located in Albuquerque, New Mexico, Jazlin gives a moving testimony. “I lost the bonding that me and him had as a young girl,” she reflects. “He used to take care of me; he used to go out and play over the summers; he used to put out the pool.” He wasn’t there during her difficult years as a teenager. He missed her high school graduation. She only has the chance to talk to him about once a month, and then only for five minutes, as there are other family members who also want to talk to him. She had kept her father’s incarceration from friends. This video was the first time she had publicly told her story. Today, she wants to be an advocate for her father. “I’ll stand up for him and be his voice,” she says.

Roberta Rael, executive director at Generation Justice, spoke with Truthout about how Jazlin’s story made it to the FCC. The organization’s work with youth is not a “one way street,” she said, but is focused on building mutual relationships based on trust. They were not just putting young people out there “for a cause.” Over the past six years, Jazlin has produced radio and video with Generation Justice around social justice issues. “We encourage young people, especially young people of color, to speak out through media,” Rael said. “The people who are most directly impacted should be the people making the decisions about how their story gets told. It is in their own words, not interpreted by us.”

Use Those Bricks and Build a Castle

In the audience at the FCC meeting was Wandjell Harvey-Robinson, of Champaign, Illinois, also a part of the MAG-Net delegation to Washington, DC. She spoke at a press conference before the hearing. She talked about how both of her parents were incarcerated when she was in the third grade. “I didn’t necessarily know why they weren’t living with me anymore,” she recalls in a video. She says she is grateful for the FCC’s intervention so that children like her can now more easily talk to their incarcerated parents.

Wandjell volunteers with Ripple Effect, a support group for families with an incarcerated loved one. They meet at a local church to share experiences, comfort one another and write letters to those inside. At a public event they held in September, Wandjell told her story about growing up with her mom and dad in prison. She was approached by those with the Illinois Campaign for Prison Phone Justice, one of several community groups working on criminal justice issues in Urbana-Champaign, based at the Independent Media Center. A month later, she was in Washington, DC, advocating on behalf of families.

“It is high time that the families of people incarcerated get the attention due to them,” said James Kilgore, a member of the Illinois Campaign for Prison Phone Justice, and author of the new book Understanding Mass Incarceration: A People’s Guide to the Key Civil Rights Struggle of Our Time. “They are heroic examples, both for the sacrifices they make, and the love they show for their family members and the larger community.”

Prison phone justice activists expect a lawsuit will challenge the FCC’s ruling. The phone companies feel they are being negatively portrayed as the bad guys. They say the vote is a “business-ending event.”

“Use those bricks” that the phone companies and police throw at you, says Wandjell Harvey-Robinson, “and build a castle. Because we did it.”